How the G7 Can Use “Data Free Flow With Trust” to Build Global Data Governance

The G7 should develop a pragmatic agenda to bring the “Data Free Flow with Trust” initiative to life. If it doesn’t, building an open, rights-respecting, and innovative global digital economy only gets harder as China and others fill the vacuum from the lack of global digital cooperation.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Key Takeaways

Contents

Key Goals to Take DFFT From Concept to Action. 5

Put DFFT on a Firmer Footing With an Empowered Secretariat. 5

Do a Stock Take of DFFT-Related Commitments, Case Studies, and Best Practices. 7

Map How Countries Live Up to the OECD’s Trusted Access by Government to Data Initiative. 7

Develop Common Core Criteria for Country Whitelists. 11

Make the Global Cross Border Privacy Rules a Centerpiece for Global Data Privacy. 13

Make the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime a Centerpiece of the DFFT. 15

Help Law Enforcement Agencies From Developing Countries Make Cross-Border Requests for Data. 16

Develop Reasonable, Responsible, and Ethical Data Sharing Models—Starting With Health Data. 18

Introduction

G7 (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States) countries need to move the “Data Free Flow with Trust” (DFFT) initiative from a concept and talking point into an action plan.[1] Otherwise, the promise of an open, rights-respecting, and innovative global digital economy will fade. China and others will fill the vacuum created by the lack of global digital norms, rules, and agreements with policies that are both protectionist and regressive from a human rights perspective.[2] Divisions within G7 and likeminded countries make progress difficult, but not impossible. The best chance for progress is pragmatic, small-group outcomes at the G7 (and elsewhere), especially via the recently launched DFFT Secretariat at the Organization for Cooperation and Economic Development (OECD). Idealist calls for a new all-encompassing global digital organization will lead to no outcome or, even worse, a lowest common denominator set by China. Project by project, DFFT-related outcomes could be expanded to more countries and forums and adapted to more issues. Building on the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation’s (ITIF’s) report “Principles and Policies for ‘Data Free Flow With Trust,’” this post provides a series of short recommendations for G7 members and the secretariat to bring the DFFT initiative to life.[3]

Japan deserves credit for putting digital issues on the global agenda via the DFFT initiative, which was launched by former Japanese Prime Minister Abe during Japan’s hosting of the G20 in 2019. Given China’s and Russia’s membership in the G20, the G7 has become the main vehicle for trying to bring the DFFT initiative to life. Since DFFT’s launch in 2019, global competition and conflict over digital technologies and policies have only intensified, yet leading digital countries at the G7 and elsewhere still can’t demonstrate what DFFT means in practice. Discussions of DFFT cover privacy and data protection across borders, along with security and intellectual property rights protection, among other issues.[4] The United States defensive approach to DFFT reflects many factors, including the fact that it also lacks a strategy and action plan for the global digital economy (beyond aspirational calls for a free, open, and democratic Internet).[5] Meanwhile, the European Union tries to slap the DFFT label on its fundamentally flawed and untenable efforts to harmonize global privacy laws to its General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). These and other G7 members need to reset their approach to the DFFT initiative, lest it—and the opportunity for global data governance—wither away.

Genuine global data governance is still relatively new, largely undefined, and unmeasured. There are two key challenges to making DFFT a successful demonstration of global data governance: a targeted and pragmatic agenda and strong leadership and political will among a small group of likeminded countries. Many global data and digital issues are easy to conflate, thus making it harder to find potential alignment, while points of regulatory conflict continue to intensify. To stand the best chance of making progress on global data governance, ideas need to be targeted to find and build commonality and connections between different countries and regulatory systems. As the Center for Information Policy Leadership recently stated, to protect cross-border data flows, we need pragmatic solutions to build trust.[6]

Building an open, rules-based, rights-respecting, and innovative global digital economy will depend on a small group of ambitious countries working together—such as at the DFFT—in a flexible format to draw in relevant international organizations and other interested countries and stakeholders. The success of this approach is demonstrated by the Singapore/Australia/New Zealand/Chile digital economy agreements and partnerships (DEAs and DEPA); the Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data (CLOUD) Act agreements between the United States, the United Kingdom; and Australia (and potentially with Canada and the European Union); the EU-U.S. Trade and Technology Council (TCC); the Global Cross Border Privacy Rules (CBPR) initiative; and the OECD’s AI Principles and Declaration on Government Access to Personal Data Held by Private Sector Entities.[7]

Small-group initiatives between ambitious partners do not ensure success, but they do make success more likely. Conflict between the United States and EU at the TTC show that while parties may be broadly aligned geo-strategically, when it comes to action, progress remains difficult. Despite this, bringing DFFT to life via a small-group approach remains a far better—and more realistic—option than idealist and impractical calls for a multilateral “Global Data Organization” or a United Nations–based initiative like the Global Digital Compact.[8] Not only is there no global consensus on the broad, diverse, and dynamic data and digital policies and technologies, but there’s growing geopolitical conflict over them. Nor is there likely to be agreement anytime soon. The highly problematic negotiations for a United Nations (UN) Cybercrime treaty or Russia’s proposal for a UN Convention on International Information Security provides a reality check for such idealist recommendations.[9] The same could be said for the idea for a far-reaching Digital Stability Board or UN-based global institutional framework to cover the full gamut of issues, from taxes to artificial intelligence (AI) ethics to competition policy—as if there’s alignment on even a small number of these issues, when there isn’t.[10]

Japan, the United States, Europe, and other leading digital players still can’t say what the Data Free Flow with Trust initiative means in practice. G7 members need an action plan to bring it to life, lest the initiative—and a key opportunity for global data governance—wither away.

Calls for a new international organization are understandable—global issues are best addressed through a global forum—but there simply isn’t enough support for the type of foundational policies the United States, EU, and others would want embedded at the multilateral level. Discussions at the UN may help developing countries build a better understanding about data and digital issues so that a broader, stronger foundation for consensus emerges in the future (though this is far from a given). The UN and leading digital countries certainly need to do more to help developing countries with digital issues. Australia, Japan, Singapore, Switzerland, and the OECD’s efforts to help developing countries in plurilateral World Trade Organization (WTO) e-commerce negotiations show the value of using capacity building to help developing countries understand why they can and should make more ambitious digital policy commitments.[11] However, the current lack of consensus at the multilateral level means that if the UN becomes the vehicle for potential action, it’ll revert to the lowest common denominator, and at the moment, that’s worse than no outcome at all.

In contrast, small group initiatives such as those at the DFFT at the G7 would provide the critical foundation for broader debate, adaptation, and adoption to expand to more issues and countries. A foundation between likeminded partners would make it much easier to shape global norms and principles with the 100-plus developing countries that have not decided which approach to digital governance they will take (in terms of the general models presented by China, the EU, and the United States). These countries will be far more susceptible to bad digital policies in the absence of good ones demonstrated under a successful DFFT initiative. The Biden administration’s Declaration for the Future of the Internet faces the same challenge.[12] If high-level principles fail to move to action, it won’t make an impact.

Key Goals to Take DFFT From Concept to Action

The 2023 G7 ministers meeting provided a conceptual framework to bring DFFT to life with pragmatism, flexibility, and interoperability. Ministers stated that “trust should be built and realized through various legal and voluntary frameworks, guidelines, standards, technologies and other means that are transparent and protect data,” and that their goal is to “build upon commonalities, complementarities, and elements of convergence between existing regulatory approaches and instruments enabling data to flow with trust in order to foster future interoperability.”[13]

The 2023 “Annex on the G7 Vision for Operationalizing DFFT and its Priorities” highlighted four key issues:

▪ Data localization: DFFT should deliver tangible progress in understanding the economic and societal impact of data localization measures, while taking into account varied approaches to data governance and legitimate public policy objectives.

▪ Regulatory cooperation: DFFT should promote work to identify commonalities in regulatory approaches to cross-border data transfers and data protection requirements as well as facilitate cooperation on privacy-enhancing technologies (PETs), approaches such as model contractual clauses certification, and accessible regulatory information and best practices, such as enhancing transparency.

▪ Trusted government access to data: DFFT should build awareness of the OECD Declaration on Government Access to Personal Data Held by Private Sector Entities among private sector entities and other nations encouraged to sign up to its principles. The DFFT secretariat should develop a shared understanding on appropriate risk-based approaches for preventing any government access to personal data that is inconsistent with democratic values and the rule of law, and is unconstrained, unreasonable, arbitrary or disproportionate.

▪ Data sharing: COVID-19 and other global issues have demonstrated the value and need for like-minded partners to find consensus on approaches to data sharing in priority sectors such as health care, climate technology, and mobility (e.g., geospatial information platform for autonomous mobilities) to foster innovation and economic growth. The annex upheld the role of technology and use cases thereof such as digital credentials and identities in facilitating data sharing as a part of our efforts to operationalize DFFT. It also noted improved data use is a major strategic opportunity for economic growth.[14]

In that context, the following are specific ideas to take DFFT from concept into action.

Put DFFT on a Firmer Footing With an Empowered Secretariat

DFFT needs institutional support to move discussions from concept to action. Thankfully, the United States and other G7 members recently endorsed the establishment of the Institutional Arrangement for Partnership (IAP) within the OECD to bring governments and stakeholders together to operationalize DFFT through principles-based, solutions-oriented, evidence-based, multistakeholder and cross-sectoral cooperation.

G7 ministers were right in stating that a secretariat is needed to operationalize DFFT. There are gaps in international governance to operationalize DFFT due to its cross-sectoral nature, and there is a need for a new mechanism to bring governments and stakeholders together.[15] The DFFT secretariat should support targeted and pragmatic discussions between governments. The goal for the secretariat should be to support government action on foundational issues for global data governance, which could then form the basis for broader discussions at the OECD and elsewhere. The secretariat should bring in other stakeholders (industry, civil society, academia, etc.) where needed, but it should primarily be a forum for G7 governments to work together, as otherwise it runs the risk of turning into another unproductive talk shop. G7 members could designate working-level government officials to guide the secretariat on an ongoing basis to ensure progress and discussions are targeted to what’s of interest to respective governments and doesn’t just happen in fits and spurts in the lead-up to ministerial meetings. In this way, the secretariat would provide continuity and permanence for the DFFT initiative and associated discussions, which otherwise wax and wane depending on the G7 (or even worse, G20) host country.

G7 ministers were right in stating that a secretariat is needed to operationalize DFFT. There are gaps in international governance to operationalize DFFT due to its cross-sectoral nature, and there is a need for a new mechanism to bring governments and stakeholders together.

The IAP should not be some new, sprawling global organization. It should reflect the OECD’s strengths given its technocratic focus, sophisticated research capabilities, targeted and directed work, and extensive experience with digital policy issues and collaboration with international forums such as the G20, G7, and WTO. The OECD-based IAP would leverage the OECD’s existing work on DFFT-related discussions, such as data localization, cross-border cooperation between data protection and privacy agencies, enhancing data sharing, and privacy enhancing technologies, among other issues. The IAP should complement the bigger membership and broader agenda of the new OECD Global Forum on Technology (which is working to ensure it avoids unnecessary overlap with the secretariat and other OECD work).[16]

The IAP reportedly will be modeled off the Financial Stability Board (FSB), which was established in 2009 to ensure broad, leader-level coordination of the global financial system during the global financial crisis. The FSB is a good reference point for the IAP. The vision is of a small, focused, and institutionally supported leader’s forum providing the direction and agenda for the DFFT initiative, such as identifying and prioritizing major issues and best practices, discussing potential new mechanisms, and identifying issues that require more research and discussion by the IAP (which may happen via tasking to relevant international organizations and other bodies).

Once up and running, the IAP should become a leading advocate and educator for the principles, best practices, and initiatives that demonstrate DFFT. For example, the IAP could work with third-world countries to socialize the OECD’s trusted access to government principles. The IAP could engage with the African Union secretariat and members, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and other regional groupings to explore how these principles play out among their respective members. These respective regional organizations and their members are all at different stages with this issue, so targeted and tailored IAP engagement would lay the foundation for practices and policies that relate to their respective situations.

Do a Stock Take of DFFT-Related Commitments, Case Studies, and Best Practices

DFFT countries should task the IAP with performing a stock take on DFFT-related developments, case studies, and best practices to provide evidence of its application and options for further expansion. A stock take would provide an overview of what has been accomplished, what could be revised and expanded, and what gaps remain and need new initiatives.

There have been several major developments since DFFT launched in 2019. These include the forthcoming EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework, the OECD Declaration on Government Access to Personal Data Held by Private Sector Entities, and the CLOUD Act agreements between the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia.[17] It also includes the Global CBPR initiative. Australia, Singapore, New Zealand, Chile, and others have also launched digital economy agreements that include regulatory cooperation on data flows, AI, digital trade, and other issues. Besides these major initiatives, the stock take could investigate smaller-scale case studies and pilot projects countries have used that also get at underlying issues related to the concept of DFFT, such as regulatory cooperation and data exchanges, joint enforcement/investigations, and cross-border research data models (some potential related ideas are detailed ahead).

Map How Countries Live Up to the OECD’s Trusted Access by Government to Data Initiative

Countries should task the IAP with preparing and publishing a report on how DFFT countries live up to the principles in the new OECD Declaration on Government Access to Personal Data Held by Private Sector Entities (also known as the “Trusted Access by Governments to Personal Data” initiative).[18] This first-of-its-kind agreement should be foundational to the DFFT initiative, as concerns about government access to data—whether for surveillance, law enforcement, or other purposes—underpins many concerns about data privacy and data flows. It’s critical that the G7 ensure this hard-fought OECD initiative on trusted government access to data doesn’t just become a set of principles that exist only on paper and not in practice.

This mapping study should analyze and publish the laws and regulations (but not technical surveillance practices) that show how countries with different cultural, legal, and political systems meet these common principles around trusted government access to data. Such a map would provide a real-world guide for non-member countries to highlight how they too can live up to these common principles and what changes they may need to make to do so. For example, it’d be of immediate use to those countries working through OECD accession, such as Argentina, Brazil, Bulgaria, Croatia, Peru, and Romania. The map would also provide a useful basis for building out the OECD and IAP’s engagement on the critical issue of government access to data with non-OECD countries.

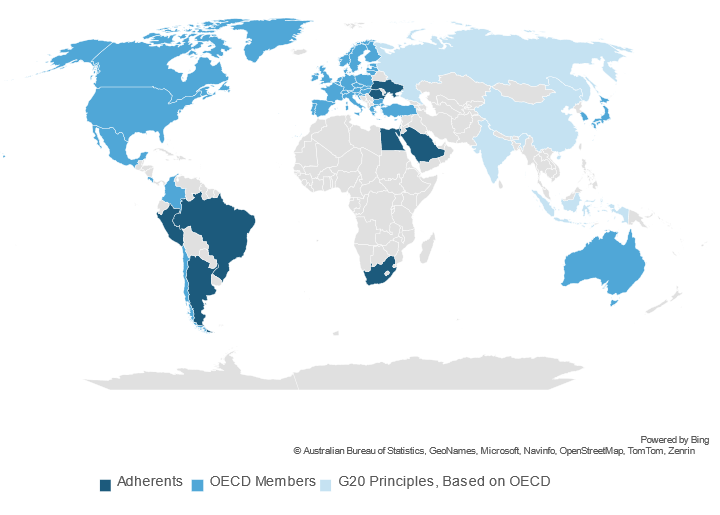

The OECD’s ongoing work to bring the OECD Principles on AI—the first intergovernmental standard on AI—to life is a close example of what needs to happen for the OECD Declaration on Government Access to Personal Data Held by Private Sector Entities (and is another reason why the OECD is a good choice to be the IAP for DFFT). At launch in 2019, 36 member countries, along with Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Peru, and Romania, signed up for the OECD Principles on AI (figure 1).[19] The principles aim to ensure AI systems are designed to be robust, safe, fair, and trustworthy. Like the OECD government access to data principles, these AI principles were high level, but they put some lines on the roadway for everyone to work between in subsequent discussions, regulations, and laws. The principles comprise five values-based principles for the responsible deployment of trustworthy AI and five recommendations for public policy and international cooperation. Countries are now working on how to operationalize these principles with each other, including via a focus on creating a risk-based AI management framework.[20] As of April 2023, 55 countries reported national AI strategies to steer trustworthy AI development and deployment in the OECD AI Policy Observatory. Furthermore, more than 890 related policy initiatives across 69 jurisdictions have also been recorded in the policy hub.

Figure 1: Adherents to the OECD AI Principles[21]

Map How China and Other Countries Contravene DFFT and OECD Principles for Privacy-Respecting Data Flows and Governance

The balance in former Japanese Prime Minister Abe’s DFFT is its duality—that data flows where there is trust.[22] There is clearly no real trust about data flows to China. Policymakers admit (behind closed doors) that DFFT (now) is largely defined not by what it is for, but by what it is against: China. Putting this mapping idea on the agenda would finally be saying the quiet part out loud—and in doing so, provide much needed reference material to help firms and regulators understand the risk from excessive and arbitrary government access to data in China and other problematic countries.

The IAP (or if it’s deemed too sensitive, another organization tasked by the IAP) should map how countries such as China and Russia exemplify the counterpoint in terms of how countries actively undermine the principles that make up both the DFFT and the OECD trusted government access to data initiatives. It would be like the European Data Protection Board’s detailed analysis of government access to data in China, Russia, and India, but benefit from more detailed and comparative analysis (e.g., to the OECD trusted access to data principles).[23] There remains a lack of both transparency and details about how exactly China exercises the broad legal discretion its laws provide the government to access data. This research could help plug this major gap. For example, this could include research into China’s government access to data both domestically and extraterritorially. China’s Cybersecurity Law, Personal Information Protection Law, and Data Security Law provide the legal foundation for data governance in China, but also still allow for broad discretion by the state.[24]

Build Tools for Interoperability: Common Contractual Clauses, Common Criteria for Assessing Countries for Whitelists, and the Global Cross-Border Privacy Rules Initiative

DFFT countries should standardize the increasingly complex and conflicting set of core transfer tools—namely, contractual clauses and lists of comparable/adequate countries other countries use to allow data flows—so firms (and regulators) focus on good data practices as opposed to the administrative exercise (i.e., bureaucracy) of legal compliance. Likewise, DFFT countries should discuss how the new Global CBPR initiative can play a role as a tool to build interoperability between different data privacy systems.

The overarching goal for DFFT countries should be to build a set of clear, common, and predictable legal tools for personal data transfers. In OECD surveys, businesses have made clear that greater transparency, predictability, and cross-sectoral consistency in transfer requirements would facilitate more effective compliance and protection for individuals.[25] The goal should be to simplify the growing complexity among legal tools. For example, countries often make changes to common contractual clauses—which firms must use for data transfers—that do not materially change legal compliance but add complexity and bureaucracy. Multiply this contractual differentiation across dozens of countries every year and the complexity and administrative rapidly grows, with little actual impact on data practices and data subjects. Simplifying and improving these tools would build genuine interoperability for data between different regulatory regimes.

DFFT countries should focus on simplifying the increasingly complex and conflicting set of core transfer tools—especially contractual clauses and white lists of comparable/adequate countries—so firms (and regulators) can focus on good data practices as opposed to administrative compliance.

The most realistic goal for global data governance is building a diverse tool kit of legal tools and agreements that provide interoperability between different, but broadly similar, legal systems. Interoperability, as opposed to harmonizing to one data privacy law, is the most realistic goal for global data governance, as it accounts for the fact that countries have differing legal, political, and social values and systems.[26] It also reflects the fact that there is no silver bullet, no single global law, to solve for differential and conflicting data governance systems. DFFT countries should focus on building standardized tools to enhance interoperability.

The secretariat and G7 countries should focus on three core tools to facilitate interoperable data privacy regimes: developing core criteria to make country whitelists consistent and meaningful; standardized provisions for contractual clauses; and explaining and socializing Global CBPR.

Develop Standard Contractual Clauses to Build Interoperability Between Different Data Privacy Systems

DFFT countries (via the IAP) should discuss how to standardize common clauses for the contracts a growing number of countries and regions allow firms to use as a tool to ensure privacy-respecting data transfers.

Contracts are among the most-used tools to manage privacy and other legal compliance related to data flows. Contracts set out parties’ responsibilities regarding data transfer, mandating to a greater or lesser extent what information those parties must provide to one another, members of the public, and relevant government authorities, while also including other issues such as the need to evaluate the laws of destination jurisdictions.

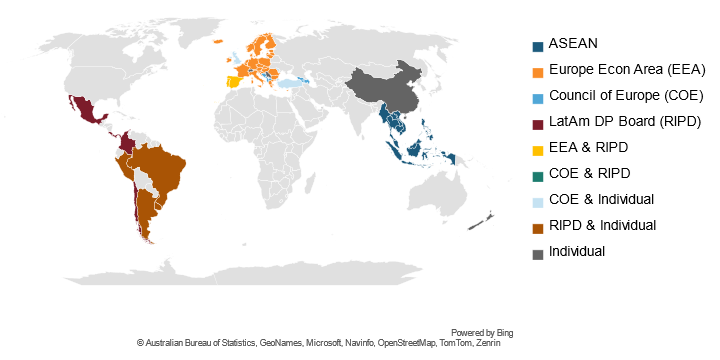

Despite their names, standard contractual clauses (SCCs) or model contractual clauses (MCCs) can be very different. There are at least 20 draft, template, or standardized contractual clauses or undertakings for international data transfers covering transfers from 71 countries (figure 2).[27] As the Future of Privacy Forum’s recent paper “Not-So-Standard Clauses” details, model contractual clauses are not standard and differential approaches are proliferating around the world: the EU’s SCCs, ASEAN MCCs, the Ibero-American Data Protection Network’s (known as RIPD) model transfer agreement, the Council of Europe’s (CoE) Convention 108+, among many other country-specific contractual clauses.[28]

Figure 2: There are at least 20 draft, template, or standardized contractual clauses or undertakings for international data transfers covering transfers from 71 countries[29]

Firms are facing administrative overload—and fatigue—over data transfers given the proliferation of different and conflicting contractual requirements. Contracts that used to be a few dozen pages long are now hundreds of pages as firms add more and more attachments to cover more and more country-specific contractual requirements. Not only does this create a significant legal and administrative burden for firms—especially small and medium-sized ones—but it also absorbs resources and attention that otherwise might go to actual privacy and data management practices. This is especially true for the EU’s SCCs that make firms responsible for the difficult task of analyzing and addressing the risk (even if hypothetical) of government access to data.

Firms are facing administrative overload—and fatigue—over the legal compliance involved in data transfers. This creates a significant legal and administrative burden for firms that absorbs resources and attention that otherwise might go to actual privacy and data management.

The IAP should convene a multistakeholder forum with data privacy agencies and relevant nongovernment and industry organizations to develop common, risk-based approaches to core contractual clauses. Standardized legal provisions would build practical interoperability for firms managing data privacy issues across different, but likeminded, countries. For example, the United Kingdom’s Information Commissioner’s Office created an international data transfer addendum for firms as part of the European Commission’s standard contractual clauses. Instead of each UK firm developing its own clauses, this provides a standardized approach for UK firms to comply with the EU’s GDPR.[30] Ideally, the IAP could work to develop standardized clauses multiple data privacy agencies would accept, thus greatly simplifying legal compliance and helping shift the focus back to what matters: actual good data privacy practices.

Develop Common Core Criteria for Country Whitelists

DFFT countries (via the secretariat) should discuss how to develop common risked-based criteria to use as part of the country-based “white lists” they use to designate where personal data can and can’t be transferred. This would create interoperability between country lists.

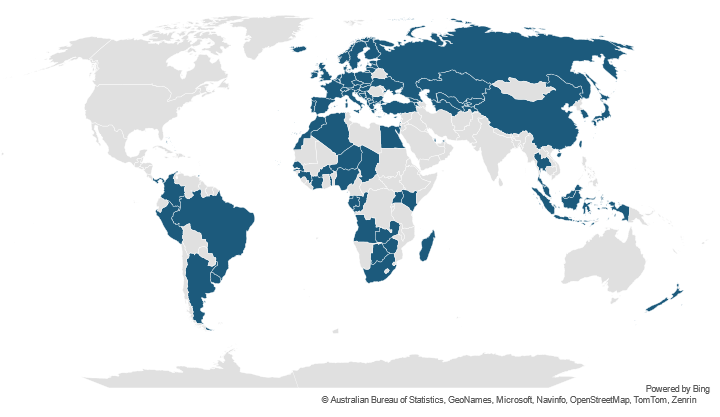

Ideally, countries would avoid using white lists, as they reveal only a limited regulatory view of how data flows, and the principle of accountability, work in practice. Firms should be held accountable, regardless of where data is transferred. Of course, regulatory agencies can highlight problematic jurisdictions to help firms determine how to maintain legal compliance. However, data transfers have little to do with the white lists many countries create. Regardless, the “spaghetti bowl” of country whitelists—there are 74 countries that designate (in one way, shape, or form) other jurisdictions as adequate or comparable—is growing in number and complexity, and thus detracting from good data privacy practices and interoperability (figure 3).[31] DFFT should develop core criteria to help rectify this.

Many countries lists lack integrity, expediency, and consistency. Countries fail to develop and apply clear, common, and consistent criteria for listing or delisting other countries. In some cases, countries (e.g., Columbia) don’t have a criterion or transparency about decision-making, thus making their listing (and delisting) arbitrary. Some countries, such as Malaysia, haven’t added other countries to their lists. Some countries such as New Zealand run a public submission process to determine which countries to list, but ultimately don’t list any for fear of angering certain countries (e.g., China). This makes lists largely meaningless and arbitrary and thus difficult to use as the basis for interoperability.

Figure 3: 74 countries have some type of “white list” process for assessing other countries as being adequate or comparable[32]

DFFT countries (via the IAP and other invited stakeholders) should work to develop common criteria for how they assess countries’ data privacy systems. This would make country lists more meaningful and interoperable. It would also avoid wasting regulators’ limited resources via duplicative assessments. This could include the standardized application of the OECD privacy principles and focusing on actual harms and risks, including for assessing risks concerning government access to data. Ideally, DFFT countries would get to a point where they’d apply a common criterion and accept (all or part of) other DFFT country assessments such that DFFT country A could assess and list country B while also accepting DFFT country C’s assessment of country D.

Make the Global Cross Border Privacy Rules a Centerpiece for Global Data Privacy

The DFFT’s principles will be brought to life in a meaningful way via the forthcoming Global CBPR initiative, which is exactly the type of interoperable, accountability-based, and scalable model for trusted data flows. Of the G7, Canada, Japan, the United Kingdom, and United States are all Global CBPR members. It also includes several other likeminded members (e.g., Australia, Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan), along with a few other new members and dozens of observer countries.[33]

Global CBPR provides a privacy certification that enables companies to demonstrate their compliance with government-approved requirements for data protection, backed by a review of those protections by a third party (known as an accountability agent). The Global Forum was founded to “promote interoperability and help bridge different regulatory approaches to data protection and privacy.”[34] Its goal is to promote the free flow of data while maintaining robust data protections for consumers regardless of jurisdiction. It’s based on the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) CBPR, but with several reforms. CBPR had to leave APEC and go global as China and Russia (both APEC member economies) disliked it (even though they did not join the APEC CBPR) and were committed to undermining it.

Global CBPR is focused on how non-EU countries can seek to deal with trusted data flows among themselves. The EU obviously has its own approach. Putting Global CBPR on the DFFT agenda would help ensure the EU and other DFFT-adjacent countries fully understand the initiative. Ideally, at some point in the future once Global CBPR is well and truly up and running, it would be worthwhile to see how it could potentially build a bridge between the Global CBPR and the EU’s GDPR.

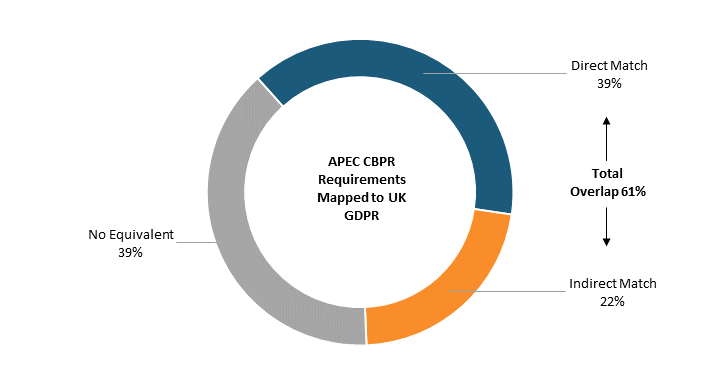

Disappointingly, European Commission officials still speak dismissively about Global CBPR, but at least the EU has publicly stated that it is at least ready to learn more about the initiative.[35] The Department of Commerce has stated that there is considerable overlap between existing models.[36] A Center for Information Policy Leadership study shows this: There is an overlap of 61 percent in relevant requirements between GDPR and the APEC CBPR System (the now-Global CBPR System) and an overlap of 67 percent between GDPR and Privacy Shield (the soon to be EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework) requirements (figure 4). Furthermore, the gap does not necessarily indicate substantively less protection than that provided by the GDPR, as some missing provisions reflect institutional and procedural issues.[37]

Figure 4: Overlap relevant requirements of GDPR and CBPR[38]

The EU (fairly) criticized APEC CBPR for the lack of firms signing up for it, but this is one of several issues Global CBPR will address in reforms before its launch. Hopefully, if a broad and diverse range of countries commit to a new and improved Global CBPR, the EU will come around and work in good faith with its likeminded partners on building a truly global and interoperable data privacy system.

Sector-Specific Outcomes

Task Financial Authorities With Developing Common Principles and Provisions to Support Data Flows and Regulatory Access to Data

For financial regulatory authorities, trusted data flows mean access to data from firms when they need it, regardless of where data is stored. DFFT countries’ finance ministries, central banks, and trade agencies should develop common practices, principles, regulatory guidance, and agreements to provide a higher, common level of certainty to ensure regulators have the access they need, while signaling to firms that they can freely transfer data.

Countries such as China, India, Indonesia, Turkey, Vietnam, and Russia use (or have tried to use) the lack of transparency and rules around financial data governance as cover to enact restrictions on data transfers for protectionism and other purposes.[39] These countries try to justify localization on the basis that it’s necessary for regulatory oversight—when it isn’t.

Financial agencies are naturally cautious about initiatives that impact their regulatory sovereignty given the stakes involved in ensuring financial stability. However, new initiatives support regulatory sovereignty in providing certainty to both firms and regulators. Financial regulators need to create new rules and cooperation to protect data flows if they want to avoid running into data localization policies that would prevent them from accessing data during regular due-diligence reviews or a financial crisis.

DFFT work on financial data governance should focus on ensuring firms’ data remains accessible, regardless of where it’s stored. Australia, Canada, United States, Mexico, Hong Kong, Singapore, the United Kingdom, and others have already released guidance, enacted new trade law provisions, and negotiated new memorandums of understanding (MOUs) about how financial firms can and should handle data regardless of where it is located.[40] For example, an MOU between Australian and Singaporean financial regulatory authorities makes clear that firms in one jurisdiction should provide data to the financial authorities in the other jurisdiction, while also reiterating that firms are free to transfer data between the two jurisdictions.[41] Similarly, the United States-Mexico-Canada trade agreement created a framework that allows for the free flow of financial data, but provides detailed guidance on how firms need to manage IT systems to ensure regulatory access to data.[42]

Make the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime a Centerpiece of the DFFT

DFFT countries should place greater support for the world’s first cybercrime treaty—the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime—at the top of their agenda, as doing so would demonstrate a widely accepted set of principles and practices that are aligned with the DFFT initiative.[43]

Criminal evidence today is not only digital but global, defying traditional notions of geography and territorial jurisdiction. A domestic criminal investigation—with local suspects and victims—will more often than not involve digital evidence that may make international cooperation a necessity. While the Budapest Convention was negotiated 20 years ago, its updated “Second Additional Protocol” brings it into the digital era.[44] The Second Additional Protocol is specifically designed to help law enforcement authorities obtain access to electronic evidence, with new tools including direct cooperation with service providers and registrars, expedited means to obtain subscriber information and traffic data associated with criminal activity, and expedited cooperation in obtaining stored computer data in emergencies. All these tools are subject to a system of human rights and rule-of-law safeguards.

Adding a DFFT workstream to support the Budapest Convention should be an easy sell. All G7 countries have acceded to the treaty and signed onto the second protocol. As of March 27, 2023, 68 countries have acceded to the original Budapest Convention, while 35 countries have signed onto the second protocol, which includes most of Europe plus Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Morocco, and Sri Lanka.[45]

DFFT countries should provide greater support for the world’s first cybercrime treaty—the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime—as it demonstrates the principles and practices that underpin the DFFT initiative. DFFT countries should provide more resources to encourage more countries to join the agreement.

DFFT countries should provide more coordinated advocacy, support, and engagement with countries on joining the Budapest Convention and the second protocol. The IAP, along with a subgroup of representatives from each member’s respective law enforcement and justice agencies, could establish a partnership with the Budapest Convention’s Cybercrime Program, which provides advice and technical assistance to help countries join and implement the Budapest Convention.[46] The EU is the top donor, followed by the United States, to the Cybercrime Program’s total budget, which, as of December 2022, totaled €39 million. Japan, Canada, and the United Kingdom also provide funding.[47] The Cybercrime Program relies on outside funding to support this crucial work, so it would inevitably benefit from greater funding and policy and political support via the DFFT.

Set Up Pilot Programs to Digitalize, Standardize, and Streamline Cross-Border Law Enforcement Requests for Data

DFFT countries need to develop new, better ways to address law enforcement’s ability to access data held in other jurisdictions, such as digitalizing, standardizing, and streamlining requests. Not every DFFT member country will end up with a CLOUD Act agreement, and even if they do, they’d still benefit from improving how they manage mutual legal assistance treaty (MLAT) requests with other likeminded countries.

Despite being slow, cumbersome, and bureaucratic, MLATs remain the dominant channel for law enforcement to make cross-border requests for data. For example, MLATs are still often managed in rubber-stamped and hardcopy formats via diplomatic third-person notes. Furthermore, the MLAT process is overwhelmed with requests, as evidence increasingly exists overseas for crimes that take place solely within a jurisdiction. For example, in 2017, the U.S. Department of Justice reported that requests by foreign governments for electronic evidence had increased by 1,000 percent over the last two decades.[48] The MLAT process needs updating beyond selective CLOUD Act agreements, which are not scalable.

DFFT countries should bring the system into the digital 21st century. DFFT countries could set up bilateral or small-group pilot projects to digitalize, standardize, and streamline cross-border law enforcement requests for data. MLATs are naturally very legalistic and involve various criteria and safeguards, so it may be challenging to do this. Therefore, it may be best to start with bilateral or small-group pilot studies to explore how to digitalize, standardize, and streamline this process (e.g., a pilot project between Japan and the United Kingdom or between the United Kingdom and Brazil). Once this has been developed, deployed, and tested, it could be further revised and expanded to more countries.

Help Law Enforcement Agencies From Developing Countries Make Cross-Border Requests for Data

DFFT member countries should help developing countries on a foundational issue for global data governance: improving law enforcement’s ability make cross-border requests for data (the topic of a forthcoming ITIF report). This could be part of the effort to support more countries signing up to the Budapest Convention and its second additional protocol.

U.S. CLOUD Act agreements (between the United States and Australia, the United Kingdom, and potentially the European Union, respectively) are great for those few countries that can meet its stringent standards, but for most countries, it may well become another point of frustration as they remain stuck using antiquated and inefficient legal tools and processes. Many developing countries either don’t have the main legal tool used for cross-border requests—MLATs—or don’t (or can’t) make use of MLAT or voluntary requests for noncontent data from digital service providers.

Human rights and corruption concerns make this a challenging issue for G7 and likeminded countries to address compared with improving how they manage requests among themselves. Law enforcement and justice agencies in developed countries are acutely aware of the risk of providing data and assistance to countries that may use it for political and other non-law enforcement purposes. However, more developing countries will revert to data localization and other restrictive and regressive human rights practices (as localization facilitates easier surveillance) if they are not provided help to address a legitimate issue: having only a slow and inefficient process to access digital evidence held in another jurisdiction.

DFFT work on this issue could be as simple as getting respective law enforcement and justice agencies, or even the Budapest Convention’s Cybercrime Program, to help develop and use a uniform request format for law enforcement’s use. The lack of template is one of the causes for delay in the handling of MLA requests that have poorly or oddly formatted requests. It could also include helping developing countries set up trusted intermediaries to authenticate MLATs, as many of these countries (especially small ones) don’t have MLATs—and thus, those that receive requests often struggle to authenticate them via a legitimate law enforcement agency (and not some bad actor).[49] It could also include setting up pilot project fast lanes that allow motivated and likeminded developing countries that agree to make domestic reforms that ensure clear and high-standard requests to have their requests treated in a prioritized manner.

Task Trade Agencies With Developing and Deploying Provisions for Digital Regulatory Best Practices

The DFFT should focus on what trust means in the context of good regulatory practices—open, transparent, and evidence-based policies that are developed, implemented, and come into effect over a reasonable timeframe. DFFT countries should task the IAP and a subgroup of respective trade agencies with developing model provisions on digital regulatory best practices to use in trade engagements and other tools around the world.

Countries hide measures that undermine data flows, data privacy, cybersecurity, and human rights through opaque, closed, and rushed policymaking processes. For example, regulations for Vietnam’s cybersecurity law (which included data localization and other problematic policies), had been drafted, revised, and pending for years, only for Vietnam to suddenly enact it and make it effective six weeks later.[50] In Pakistan, officials didn’t share or circulate outdated drafts of the country’s highly problematic cybercrime law before trying to bulldoze it through parliament to avoid debate and scrutiny.[51]

Good digital regulatory-making provisions act as a safeguard against bad digital policies that undermine trade, human rights, and cooperation on legal and regulatory issues. Policymakers should ensure that domestic measures affecting data are enacted in a transparent manner that allows opportunities for broad stakeholder input; are evidence‑based and consider the technical and economic feasibility of requirements; require the publication of impact assessments to ensure the appropriateness and effectiveness of regulatory approaches; and are targeted and proportionate and restrict trade as little as possible.[52]

Develop Reasonable, Responsible, and Ethical Data Sharing Models—Starting With Health Data

DFFT countries should work to develop common principles, processes, and model text to use in laws and regulations to support international data sharing models. The IAP could explore types of potential international data sharing models and barriers to their development. It could work to establish common data pools and guidance on best practices for responsible and ethical data collection, analysis, and sharing.

Health data stands out as a clear test case for a DFFT project. While policymakers need to be certain that health data is carefully protected, they also need to ensure that legal frameworks allow for the reasonable, responsible, and ethical sharing of data—including globally—given the enormous potential social and economic benefits of new and improved health services.[53]

DFFT countries should make global health data sharing a priority given the significant societal and economic benefits. Health firms and researchers are calling on governments to create legal and regulatory frameworks that allow for the reasonable, responsible, and ethical sharing of health data.

Researchers are calling for this type of initiative on international health data sharing. In February 2020, leading health researchers called for an international code of conduct for genomic data following the end of their first-of-its-kind international data-driven research project.[54] From screening chemical compounds to optimizing clinical trials to improving post-market surveillance of drugs, the increased use of data and better analytical tools, such as AI, hold the potential to transform health care and drug development, leading to new treatments, improved patient outcomes, and lower costs.[55] Health research is increasingly an international endeavor that depends on the aggregation and sharing of personal data. However, Australia, China, Russia, South Korea, Turkey, and the European Union all have laws that restrict the sharing of personal, health, and genomic data.[56]

Conclusion

Hopefully Japan, the United States, and other G7 countries recognize and seize the opportunity of having likeminded, value-sharing partners engaged in the DFFT initiative. It would be a strategic mistake to let this opportunity go due to bilateral differences and conflicts, which in the grand scheme of things, pale in comparison with the contrast with China and other digital authoritarian countries.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Rob Atkinson, Stephen Ezell, Daniel Castro, and the data policy experts who discussed potential ideas for the DFFT initiative. Any errors or omissions are the author’s responsibility alone.

About the Author

Nigel Cory (@NigelCory) is an associate director covering trade policy at ITIF. He focuses on cross-border data flows, data governance, and intellectual property and how they each relate to digital trade and the broader digital economy.

About ITIF

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute that has been recognized repeatedly as the world’s leading think tank for science and technology policy. Its mission is to formulate, evaluate, and promote policy solutions that accelerate innovation and boost productivity to spur growth, opportunity, and progress. For more information, visit itif.org/about.

Endnotes

[1]. “G20 Osaka Summit – Summary of Outcomes,” BMDV, https://bmdv.bund.de/SharedDocs/DE/Anlage/K/g7-praesidentschaft-final-declaration-annex-1.pdf.

[2]. Adrian Shahbaz, Allie Funk, and Andrea Hackl, “User Privacy or Cyber Sovereignty?” (Freedom House, 2020), https://freedomhouse.org/report/special-report/2020/user-privacy-or-cyber-sovereignty; Edited by Emily de La Bruyère, Doug Strub, and Jonathon Marek, “China’s Digital Ambitions: A Global Strategy to Supplant the Liberal Order” (the National Bureau of Asian Research, March 1, 2022), https://www.nbr.org/publication/chinas-digital-ambitions-a-global-strategy-to-supplant-the-liberal-order/.

[3]. Nigel Cory, Robert Atkinson, and Daniel Castro, “Principles and Policies for ‘Data Free Flow With Trust’” (ITIF, May 27, 2019), https://itif.org/publications/2019/05/27/principles-and-policies-data-free-flow-trust/.

[4]. Francesca Casalini and Shihori Maeda, Moving Forward on Data Free Flow with Trust: New Evidence and Analysis of Business Experiences, (Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2023), https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/science-and-technology/moving-forward-on-data-free-flow-with-trust_1afab147-en.

[5]. Robert Atkinson, “A U.S. Grand Strategy for the Global Digital Economy” (ITIF, January 19, 2021), https://itif.org/publications/2021/01/19/us-grand-strategy-global-digital-economy/.

[6]. “To Solve Cross-Border Data Flows We Need Pragmatic Solutions to Build Trust” (The Center for Information Policy Leadership, March 22, 2023), https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/solve-cross-border-data-flows-we-need/.

[7]. “The Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA),” MTI, https://www.mti.gov.sg/Trade/Digital-Economy-Agreements/The-Digital-Economy-Partnership-Agreement; “Australia-Singapore Digital Economy Agreement,” DFAT, https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/services-and-digital-trade/australia-and-singapore-digital-economy-agreement; “CLOUD Act Resources,” U.S. Department of Justice, https://www.justice.gov/criminal-oia/cloud-act-resources; “United States and Canada Welcome Negotiations of a CLOUD Act Agreement,” U.S. Department of Justice, press release, March 22, 2022, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/united-states-and-canada-welcome-negotiations-cloud-act-agreement; “Justice Department and European Commission Announces Resumption of U.S. and EU Negotiations on Electronic Evidence in Criminal Investigations,” U.S. Department of Justice, press release, March 2, 2023, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-and-european-commission-announces-resumption-us-and-eu-negotiations; “U.S.-E.U. Trade and Technology Council (TTC),” USTR, https://ustr.gov/useuttc; “Global Cross-Border Privacy Rules (CBPR) Forum,” Global CBPR, https://www.globalcbpr.org/; “OECD AI Principles overview,” OECD, https://oecd.ai/en/ai-principles; “Landmark agreement adopted on safeguarding privacy in law enforcement and national security data access,” OECD, press release, December 14, 2022, https://www.oecd.org/newsroom/landmark-agreement-adopted-on-safeguarding-privacy-in-law-enforcement-and-national-security-data-access.htm.

[8]. Wang Huiyao, “A World Data Organisation needed to avoid rules-based disorder,” South China Morning Post, June 8, 2022, http://en.ccg.org.cn/archives/76827; United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres, Our Common Agenda: Report of the Secretary-General (United Nations, 2021), https://www.un.org/en/content/common-agenda-report/assets/pdf/Common_Agenda_Report_English.pdf; United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres, Our Common Agenda Policy Brief 5: A Global Digital Compact – an Open, Free, and Secure Digital Future for All (United Nations, May 2023), https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/our-common-agenda-policy-brief-gobal-digi-compact-en.pdf.

[9]. Deborah Brown, “Cybercrime is Dangerous, But a New UN Treaty Could Be Worse for Rights,” Human Rights Watch, August 13, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/08/13/cybercrime-dangerous-new-un-treaty-could-be-worse-rights; Valentin Weber, “The Dangers of a New Russian Proposal for a UN Convention on International Information Security,” Council on Foreign Relations, March 21, 2023, https://www.cfr.org/blog/dangers-new-russian-proposal-un-convention-international-information-security.

[10]. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Digital Economy Report 2021 (Geneva: UNCTAD, 2021), https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/der2021_overview_en_0.pdf; Robert Fay, “Digital Platforms Require a Global Governance Framework” (Center for International Governance Innovation, October 28, 2019), https://www.cigionline.org/articles/digital-platforms-require-global-governance-framework/.

[11]. “E-Commerce JSI co-convenors announce capacity building support,” World Trade Organization, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/ecom_e/jiecomcapbuild_e.htm.

[12]. “FACT SHEET: United States and 60 Global Partners Launch Declaration for the Future of the Internet,” The White House, April 28, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/04/28/fact-sheet-united-states-and-60-global-partners-launch-declaration-for-the-future-of-the-internet/.

[13]. “G7 2023 Hiroshima Summit: Ministerial Declaration The G7 Digital and Tech Ministers’ Meeting 30 April 2023,” April 30, 2023, https://www.soumu.go.jp/joho_kokusai/g7digital-tech-2023/topics/pdf/pdf_20230430/ministerial_declaration_dtmm.pdf.

[14]. “G7 Digital and Tech Track Annex 1 Annex on G7 Vision for Operationalising DFFT and its Priorities,” https://www.soumu.go.jp/joho_kokusai/g7digital-tech-2023/topics/pdf/pdf_20230430/annex1.pdf.

[15]. “G7 2023 Hiroshima Summit: Ministerial Declaration The G7 Digital and Tech Ministers’ Meeting 30 April 2023,” April 30, 2023, https://www.soumu.go.jp/joho_kokusai/g7digital-tech-2023/topics/pdf/pdf_20230430/ministerial_declaration_dtmm.pdf.

[16]. “Global Forum on Technology,” OECD, https://www.oecd.org/digital/global-forum-on-technology/.

[17]. “Landmark agreement adopted on safeguarding privacy in law enforcement and national security data access,” OECD, press release, December 14, 2022, https://www.oecd.org/newsroom/landmark-agreement-adopted-on-safeguarding-privacy-in-law-enforcement-and-national-security-data-access.htm.

[18]. Ibid.

[19]. “Recommendation of the Council on Artificial Intelligence,” OECD, May 21, 2019, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0449.

[20]. “Artificial intelligence,” OECD, https://www.oecd.org/digital/artificial-intelligence/.

[21]. Ibid.

[22]. Hosuk Lee-Makiyama, “Data Free Flow with Trust (DFFT): Paths towards Free and Trusted Data Flows” (World Economic Forum, May, 2020), www3.weforum.org\docs\WEF_Paths_Towards_Free_and_Trusted_Data _Flows_2020.pdf.

[23]. European Data Protection Board, “Government access to data in third countries,” November, 2021, https://edpb.europa.eu/system/files/2022-01/legalstudy_on_government_access_0.pdf.

[24]. Rogier Creemers, “China’s Emerging Data Protection Framework,” SSRN, November 16, 2021, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3964684.

[25]. Francesca Casalini and Shihori Maeda, Moving Forward on Data Free Flow with Trust: New Evidence and Analysis of Business Experiences, (Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2023), https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/science-and-technology/moving-forward-on-data-free-flow-with-trust_1afab147-en.

[26]. Nigel Cory and Luke Dascoli, “How Barriers to Cross-Border Data Flows Are Spreading Globally, What They Cost, and How to Address Them” (ITIF, July 19, 2021), https://itif.org/publications/2021/07/19/how-barriers-cross-border-data-flows-are-spreading-globally-what-they-cost/; Modified definition from: Urs Gasser, “Interoperability in the Digital Ecosystem,” Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society Research Publication No2015-13, July 6, 2015, http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:28552584.

[27]. Joe Jones, “Infographic: Global data transfer contracts,” IAPP, April, 2023, https://iapp.org/resources/article/infographic-global-data-transfer-contracts/.

[28]. “Standard contractual clauses for international transfers,” European Commission, June 4, 2021, https://commission.europa.eu/publications/standard-contractual-clauses-international-transfers_en; “ASEAN Model Contractual Clauses for Cross Border Data Flows,” ASEAN.org, January, 2021, https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/3-ASEAN-Model-Contractual-Clauses-for-Cross-Border-Data-Flows_Final.pdf; Lee Matheson, “Not-So-Standard Clauses: Examining Three Regional Contractual Frameworks for International Data Transfers,” FPF, March 30, 2023, https://fpf.org/blog/fpf-report-not-so-standard-clauses-an-examination-of-three-regional-contractual-frameworks-for-international-data-transfers/; “Convention 108: Model Contractual Clauses for the Transfer of Personal Data,” Council of Europe, March 3, 2023, https://rm.coe.int/t-pd-2022-1rev8-contractual-clauses-transborder-flows-03mar23-2758-025/1680aa72a6.

[29]. Joe Jones, “Infographic: Global data transfer contracts,” IAPP, April, 2023, https://iapp.org/resources/article/infographic-global-data-transfer-contracts/.

[30]. “International data transfer agreement and guidance,” The Information Commissioner’s Office, February 2, 2022, https://ico.org.uk/for-organisations/guide-to-data-protection/guide-to-the-general-data-protection-regulation-gdpr/international-data-transfer-agreement-and-guidance/.

[31]. Joe Jones, “Infographic: Global adequacy capabilities,” IAAP, March, 2023, https://iapp.org/resources/article/infographic-global-adequacy-capabilities/.

[32]. Ibid.

[33]. “Global Cross-Border Privacy Rules Declaration,” Department of Commerce, https://www.commerce.gov/global-cross-border-privacy-rules-declaration; “Australia joins the Global Cross-Border Privacy Rules Forum,” Australia’s Attorney-General, press release, August 17, 2022, https://ministers.ag.gov.au/media-centre/australia-joins-global-cross-border-privacy-rules-forum-17-08-2022.

[34]. Ibid.

[35]. Cobun Zweifel-Keegan on Twitter, https://twitter.com/cobun/status/1532734212146507.

[36]. “The Global Cross Border Privacy Rules Forum,” IAPP, June 7, 2022, https://iapp.org/news/video/the-global-cross-border-privacy-rules-forum/.

[37]. For example: Exemptions to notice to individuals where data has not been collected directly from them (GDPR Article 14): The CBPR does not contain notice requirements for organizations that collect information about individuals from sources other than the individuals themselves. Consequently, the CBPR does not contain exemptions to this requirement. However, the lack of exemptions here does not mean that this non-match must be bridged with the GDPR. Publishing Data Protection Office (DPO) contact details (GDPR Article 37(7)): There is no match to the GDPR requirement to publish the contact details of the DPO and communicate them to the Commissioner but this does not necessarily mean that the CBPR is less protective. Under the CBPR applicants must still provide a “Contact Point” regardless of whether this is a DPO or not. Administrative fines and penalties (GDPR Articles 83 and 84): Administrative fines and penalties as described in the GDPR are subject to the domestic law of the participating CBPR country and are enforceable by privacy enforcement authorities in those jurisdictions. As a result, such remedies are not specified in the CBPR program requirements. However, under the CBPR, the official DPAs in participating jurisdictions can impose their own set of sanctions, including administrative fines under their legal framework, including redress in court. “APEC Cross-Border Privacy Rules Requirements and EU-U.S. Privacy Shield Requirements Mapped to the Provisions of the UK General Data Protection Regulation” (Center for Information Policy Leadership), www.informationpolicycentre.com/uploads/5/7/1/0/57104281/cipl_study_-_apec_cbpr_system_and_eu-us_privacy_shield_mapped_to_uk_gdpr.pdf.

[38]. Ibid.

[39]. “Storage of Payment System Data,” Reserve Bank of India, April 6, 2018, https://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/NotificationUser.aspx?Mode=0&Id=11244; “Regulation Number 19/8/PBI/2017 – National Payment Gateway,” Reserve Bank of Indonesia, 2017, https://www.amcham.or.id/images/amcham_updates/Bank%20Indonesia%20Regulation%20on%20National%20Payment%20Gateway.pdf; “Law on payment and security settlement systems, payment services, and electronic money institutions,” Banking Regulation and Supervision Agency, June 27, 2013, https://web.archive.org/web/20200706163411if_/https:/www.bddk.org.tr/ContentBddk/dokuman/mevzuat_0140.pdf; “Comments in Response to Executive Order Regarding Trade Agreements Violations and Abuses,” ITI, https://www.itic.org/dotAsset/9d22f0e2-90cb-467d-81c8-ecc87e8dbd2b.pdf; Vladimir Kanashevsky, “Use of Public Cloud Services by Russian Financial Services Institutions,” Pierstone, November 15, 2017, https://pierstone.com/use-of-public-cloud-services-by-russian-financial-services-institutions/.

[40]. “United States – Singapore Joint Statement on Financial Services Data Connectivity,” joint statement, Treasury Department, February 5, 2020, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm899; “Circular to Licensed Corporations - Use of external electronic data storage,” Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission, October 31, 2019, https://apps.sfc.hk/edistributionWeb/gateway/EN/circular/intermediaries/supervision/doc?refNo=19EC59.

[41]. “Memorandum of Understand: Australian Securities and Investment Commission and the Monetary Authority of Singapore,” ASIC, https://download.asic.gov.au/media/2067384/monetary-authority-of-singapore-mou-2014.pdf.

[42]. Nigel Cory and Stephen Ezell, “Comments to the U.S. International Trade Commission Regarding the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement” (ITIF, December 17, 2018), https://itif.org/publications/2018/12/17/comments-us-international-trade-commission-regarding-united-states-mexico/.

[43]. Jennifer Daskal and Debrae Kennedy-Mayo, “Budapest Convention: What is it and how is it being updated” (Cross-Border Data Forum, July 2, 2020), https://www.crossborderdataforum.org/budapest-convention-what-is-it-and-how-is-it-being-updated/.

[44]. “Convention on Cybercrime,” Council of Europe, https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list?module=treaty-detail&treatynum=185.

[45]. “Chart of signatures and ratifications of Convention on Cybercrime,” Council of Europe, https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list?module=signatures-by-treaty&treatynum=185; “Chart of signatures and ratifications of Second Additional Protocol to the Convention on Cybercrime,” Council of Europe, https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list?module=signatures-by-treaty&treatynum=224.

[46]. “Cybercrime Programme Office,” Council of Europe, https://www.coe.int/en/web/cybercrime/cybercrime-office-c-proc-.

[47]. “Council of Europe Office on Cybercrime in Bucharest: C-PROC activity report for the period October 2021 – December 2022,” Council of Europe, January 9, 2023, https://rm.coe.int/sg-inf-2023-1-c-proc-activity-report-oct2021-dec2022/1680a9bf3a.

[48]. “Department of Justice, Criminal Division: Performance Budget FY2017 President’s Budget,” Treasury Department, https://www.justice.gov/jmd/file/820926/download.

[49]. “Two ways that smaller countries could participate in emerging global systems for transfer of electronic evidence” (Cross Border Data Forum, May 30, 2019), https://www.crossborderdataforum.org/two-ways-that-smaller-countries-could-participate-in-emerging-global-systems-for-transfer-of-electronic-evidence/.

[50]. Manh Hung Tran, “Vietnam: Issuance of Decree Implementing the Cybersecurity Law,” Baker McKenzie blog, August 17, 2022, https://www.connectontech.com/vietnam-issuance-of-decree-implementing-the-cybersecurity-law/.

[51]. Farieha Aziz, “Pakistan’s cybercrime law: boon or bane?” (Heinrich Boll Stiuftung, February 14, 2018), https://www.boell.de/en/2018/02/07/pakistans-cybercrime-law-boon-or-bane.

[52]. “Data Free Flow with Trust (DFFT): Paths towards Free and Trusted Data Flows” (World Economic Forum, May, 2020), https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Paths_Towards_Free_and_Trusted_Data%20_Flows_2020.pdf.

[53]. Nigel Cory and Philip Stevens, “Building a Global Framework for Digital Health Services in the Era of COVID-19” (ITIF, May 26, 2020), https://itif.org/publications/2020/05/26/building-global-framework-digital-health-services-era-covid-19/.

[54]. Mark Phillips et al., “Genomics: data sharing needs an international code of conduct,” Nature, 578, 31–33 (2020), doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-00082-9.

[55]. Joshua New, “The Promise of Data-Driven Drug Development,” Center for Data Innovation, September 18, 2019, https://datainnovation.org/2019/09/the-promise-of-data-driven-drug-development/.

[56]. Tania Rabesandratana, “European data law is impeding studies on diabetes and Alzheimer's, researchers warn,” Science, November 20, 2019, https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2019/11/european-data-law-impeding-studies-diabetes-and-alzheimer-s-researchers-warn.