The Administration Should Disregard Progressives’ Unfair Attacks on Its Digital Trade Agenda

Some progressive senators and House members, as well as a swath of anti-tech, anti-trade advocates are reflexively attacking the Biden administration’s efforts to negotiate new digital trade rules in the Indo Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) on the assumption that the more foreign countries can weaken U.S. technology firms, the better off America will be. Never mind that the Biden administration’s central goal is to extend foundational trade principles such as non-discrimination to digital commerce and align IPEF’s provisions with existing U.S. laws and trade agreements. Faced with the choice of winning global market share for U.S. tech firms—which improves the U.S. trade balance, spurs growth, and supports good jobs—or enabling foreign governments to cut U.S. tech firms down to size to protect their own domestic firms, whatever the consequences, these elected officials clearly seek the latter.

Exhibit A came last month in a letter to U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai and Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo from Sens. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), Amy Klobuchar (D-MN), Sherrod Brown (D-OH), and Richard Blumenthal (D-CT), along with Reps. Jan Schakowsky (D-IL), David Cicilline (D-RI), and Rosa DeLauro (D-CT). The letter was ostensibly about digital trade negotiations with the countries involved in IPEF, but it also attacked digital trade much more broadly, roping in a slew of issues related to antitrust and competition policy that the members have unsuccessfully pursued in Congress, from forcing tech firms to pay news outlets to prohibiting self-preferencing. This amounts to an end run: Unable to enact their anti-innovation agenda in the democratic forum of the U.S. Congress, these members now want to enlist foreign governments in an effort that will reduce the global market share of U.S. technology companies.

Faced with the choice of winning global market share for U.S. tech firms—which improves the U.S. trade balance, spurs growth, and supports good jobs—or enabling foreign governments to cut U.S. tech firms down to size to protect their own domestic firms, whatever the consequences, these elected officials clearly seek the latter.

In the global battle with China for leadership in technology and innovation, these attacks are economically ill-advised, to say the least. Unfortunately, their impact radiates beyond just the IPEF negotiations; the attacks also influence the administration’s digital policy and e-commerce agendas at the U.S.-EU Trade and Technology Council and the World Trade Organization. So, it is important for the administration and bipartisan supporters of digital trade in Congress to understand the fundamental weaknesses of their arguments—and the damage they would do to the U.S. economy—and to push back by making it clear to negotiators that strong digital trade rules are squarely in the U.S. interest.

The heart of the matter is not the specific issues the letter raised, as important as they are. It is the broader question of the extent to which U.S. policy should either seek to advance U.S. interests—including those of U.S. companies—or attack business interests presumably to help the “global proletariat.” Progressive opponents, support nearly all efforts—both foreign and domestic—that attack large firms, even if they benefit foreign workers, not Americans. Where the Warren letter urges the Biden administration not to propose anything that would conflict with the progressives’ competition agenda, this is what it is referring to.

It’s one thing for progressive politicians to push their preferred legislation in Congress, but it’s quite another to undermine the U.S. administration’s efforts to promote U.S. firms and their workers overseas via commonsense digital trade provisions, something that has been the core mission of USTR since its establishment in 1963. The letter shows a concerning disregard for the usual boundaries between domestic debates and support for the U.S. government abroad.

Parsing the Progressive Critique of Digital Trade

This post assesses the validity of the criticisms the Warren letter levels against the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework and digital trade more broadly. Spoiler alert: An objective analysis shows that the criticisms are not only incorrect, but if acted upon, would hurt U.S. trade, competitiveness, and jobs.

It’s one thing for progressive politicians to push their preferred legislation in Congress, but it’s quite another to undermine the U.S. administration’s efforts to promote U.S. firms and their workers overseas via commonsense digital trade provisions.

Invalid Argument 1: Anti-Discrimination Provisions Help Large U.S. Firms Evade Competition Policies

The centerpiece of the letter is a baseless effort to attack long-standing and foundational anti-discrimination provisions and how they would supposedly prevent the United States (and other countries) from enacting new competition and anti-trust legislation.

From the letter:

Big Tech wants to include an overly broad provision that would help large tech firms evade competition policies by claiming that such policies subject these firms to “illegal trade discrimination.” This language would provide a basis for Big Tech firms, as well as foreign governments, to attack tech policies as “illegal trade barriers” simply because they may disproportionately impact “digital products” of dominant companies that happen to be headquartered in the U.S…. It is not “trade discrimination” for the U.S. government or any of our trading partners to regulate Google, Meta, Apple, Microsoft, and Amazon to protect online competition, as tech industry groups have claimed—it is common sense, and trade-pact terms should in no way inhibit it.

These members of Congress and their anti-tech supporters ignore the fact that all the Biden administration’s digital trade agenda is trying to do is ensure the fundamental principle of non-discrimination applies to digital trade. This is the notion that trading partners treat domestic and foreign products and firms equally.

The letter cites the EU’s Digital Market Act (DMA) and Digital Services Act as examples of what the Congressmembers want to achieve, but it overlooks the primary issue that the U.S. government and others criticize these laws because they use criteria tailored to target just American firms, not large European, Japanese, Indian, or Chinese companies. As law firm King and Spalding’s analysis states:

This approach is a major departure from the normal competition policy approach which is based on ex post case-by-case enquiries to determine whether there is a case of abuse of market power or anti-competitive practices and, if so, the appropriate remedy action… The DMA tailors to U.S. companies a presumption of a negative impact on the internal market simply based on the size of the company and its market presence, without considering the impact of EU competitors with similar market power.

Anti-discrimination provisions are foundational to global trade and the agreements that govern it. It is one of the core provisions of the World Trade Organization. It only becomes a factor when countries enact policies that purposely discriminate against a firm from another country, as many U.S. trading partners do.

These members of Congress appear to believe it is “commonsense” for countries to discriminate against U.S. firms. That it’s fine when China, India, Indonesia, Korea, Nigeria, Vietnam, and others enact restrictions that use competition and other digital regulations in a thinly veiled effort to discriminate against U.S. firms and by extension boost their own domestic firms. Had the DMA’s provisions applied equally to all firms regardless of size and origin, it would not have been criticized for discriminating against American firms. Even in the hypothetical case that there was new competition legislation in the United States, it would still have to adhere to the non-discrimination principle, treating both U.S. and foreign tech firms equally.

Invalid Argument 2: Digital Trade Rules Tie the Hands of Congress and U.S. Regulators

The letter makes myriad criticisms that potential IPEF provisions would tie the hands of Congress and U.S. regulators by preventing them from enacting and enforcing further U.S. laws and regulations. This is true—in part—in that trade agreements are essentially agreements between countries to voluntarily constrain their sovereign ability to enact laws and regulations. Imagine if a trade agreement did not include such provisions: There would be vastly less global trade, something many progressives actually seek.

However, the letter’s authors use of this claim is purely partisan in that they don’t want the Biden administration to essentially build on commonsense and well-established trade law provisions and concepts for the digital economy as they think it’ll impact their ability to act.

From the letter:

Corporations are advocating that the U.S. government include rules in IPEF that would tie Congress’s and regulators’ hands and conflict with President Biden’s whole-of-government effort to promote competition.

This claim is disingenuous—these policymakers tried and failed to enact their preferred competition and other digital legislation. Unsurprisingly, U.S. trade policy reflects existing U.S. laws and regulations. In contrast to what anti-trade advocates portray, U.S. trade agreements do not often lead to changes in U.S. laws. As is the case with this letter, more often than not, criticism of U.S. trade policy is actually opposition to existing U.S. law rather than anything trade agreements do. The Biden administration obviously understands what it can and can’t make in terms of potential commitments on digital policy. It also stems from a growing body of digital trade law and policy experience (even if fruitless in terms of the U.S.’s withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership).

Unsurprisingly, U.S. trade policy reflects existing U.S. laws and regulations. In contrast to what anti-trade advocates portray, U.S. trade agreements do not often lead to changes in U.S. laws.

The truth of digital trade is far from the alternative reality that rethink Trade (an anti-tech advocacy group, which the letter cites) thinks exist where the supposed goal of U.S. digital trade policy is to “excavate the policy space out from under Congress and the administration by locking the United States and its trade partners into international rules that forbid such digital governance initiatives.” As if the Department of Commerce and the United States Trade Representative (USTR), especially USTR Katherine Tai, aren’t acutely aware of U.S. law and what they can and can’t do.

These anti-tech politicians and other opponents of digital trade ignore the fact that digital trade rules don’t stop countries from creating new digital laws and regulations related to privacy, cybersecurity, competition, and other concerns. If a nation wants to make it illegal to collect data, it can do so, as long as the result is not discriminatory against foreign firms and in favor of domestic ones. Indeed, under WTO rules, these laws and regulations cannot discriminate against foreign firms. Australia, Canada, Chile, Japan, New Zealand, and many other supporters of digital trade are not labor, human rights, consumer rights, or regulatory scofflaws, as opponents of digital trade seem to think. Digital trade provisions have not stopped these countries from enacting new digital regulations on many of the issues opponents of digital trade are supposedly worried about.

To the extent that these Senators and Representatives are concerned about U.S. competition, privacy, cybersecurity, taxation, and other digital laws and regulations, the answer is not to attack and undermine U.S. digital trade and strategic interests in the Indo-Pacific, but to pass sensible new laws and regulations. Congress has already passed tax reform, and the Biden administration is developing new regulations on artificial intelligence, cybersecurity, and other digital issues. There are ongoing debates about a comprehensive data privacy framework. However, this gets at the heart of advocates’ efforts to undermine the Biden administration’s digital trade and strategic agenda for the Indo-Pacific—they tried to achieve this on antitrust policy and failed. The letter is a distraction from this reality.

Invalid Argument 3: Digital Trade Provisions Limit the Government’s Ability to Regulate Discriminatory Artificial Intelligence

Opponents claim that digital trade provisions prevent countries, including the United States, from addressing discriminatory AI is wholly unfounded.

From the letter:

Big Tech is also calling for IPEF to include a provision that would limit governments’ ability to regulate artificial intelligence (AI) domestically. Companies are increasingly outsourcing important decisions to AI, in spite of clear evidence that it can discriminate on a massive scale. The implications are huge: black box algorithms can create inhumane and unsafe working conditions, make life-altering employment decisions, reject loan applicants for having Black sounding names, and misidentify women of color in police footage. Americans’ embrace of technology relies on their government’s ability to protect their data security and prevent digital discrimination, and Congress and regulators have taken steps to do so.”

The reality is that, should Congress seek to regulate AI, it is fully able to do that, and no trade agreement would get in the way of that as long is the regulations apply equally to domestic and foreign firms selling their AI services in the United States. If Congress passes AI regulations, just as it gives the executive branch the ability to promulgate product safety regulations on cars, toys, and medicines, foreign imports must comply with these laws, regardless of trade rules—again, as long as the laws are not intentionally discriminatory. There is clear precedence for this from the famous Danish bottle bill from the early 1990s when the Danish government banned the sale of canned beer on environmental grounds. At the time, Danish brewers only sold bottled beer. The WTO rightly struck down this rule because it was blatantly protectionist.

Invalid Argument 4: U.S. Firms Can Use Digital Trade Provisions to Transfer Data Overseas and Thereby Avoid Complying With U.S. Laws

The letter wrongly suggests that companies can bypass U.S. data privacy and other data-related laws and regulations by simply transferring data overseas and that digital trade provisions to protect the flow of data thus undermine U.S. laws.

From the letter:

Big Tech is pushing for trade rules that would allow Americans’ sensitive personal data to be sent anywhere—with little ability for Congress to limit such transfers or require that critical data be kept in the U.S. While seemingly innocuous, this means that sensitive medical records, business secrets, or critical national security information could be sent and stored anywhere in the world. This only benefits Big Tech firms seeking unlimited control over our sensitive, personal data.

If companies have legal nexus in the United States—which is clearly the case for big U.S. tech firms and most foreign technology firms selling products or services in the United States—then they are subject to U.S. law and can be held accountable for violating it, regardless of where data are stored. The U.S. Federal Trade Commission has issued large fines against Meta, Google, and many other tech firms. The ability of firms to transfer data is irrelevant in relation to their legal responsibility.

More than likely, the letter is based on bad analysis from anti-tech and -trade advocates who have fallen for the false promise of data nationalism in thinking that data is safer and more private if stored domestically—which it isn’t. As long as the company involved has legal nexus in a nation, it is subject to the privacy and cybersecurity laws and regulations of that nation. For example, foreign companies operating in the United States must comply with the privacy provisions of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), which regulates U.S. citizens’ privacy rights for health data—even if they move data outside the United States. And, if a foreign company’s affiliates overseas violate HIPAA, then U.S. regulators can bring legal action against the foreign company’s operations in the United States.

If companies have legal nexus in the United States—which is clearly the case for U.S. big tech firms and most foreign technology firms selling products or services in the United States—then they are subject to U.S. law and can be held accountable for violating it, regardless of where data are stored.

Opponents misunderstand that the confidentiality of data does not generally depend on which country the information is stored in, only on the measures used to store it securely. Data security depends on the technical, physical, and administrative controls implemented by the service provider, which can be strong or weak, regardless of where the data is stored. To prove the point: China’s high-profile hack of the U.S. Office of Management and Budget involved data stored in on-premise servers.

The Biden administration and other IPEF members like Australia, Japan, and Singapore are no doubt negotiating provisions that protect the free flow of data and prohibit measures that force firms to store data locally (a concept known as data localization). More and more countries support these trade provisions to push back against growing global digital protectionism, whereby countries enact barriers to data flows as part of efforts to protect and support local ICT companies at the expense of foreign firms. As ITIF has detailed, the number of data-localization measures in force around the world has more than doubled in four years. In 2017, 35 countries had implemented 67 such barriers. Now, 62 countries have imposed 144 restrictions—and dozens more are under consideration. Again, countries are enacting digital trade provisions to target countries using forced local data storage requirements as a way to discriminate against foreign firms and products. And because IT is one of the few industries where the United States still leads the world, such foreign protectionist efforts pose a real threat to the U.S. economy and U.S. jobs.

Invalid Argument 5: Digital Trade Rules on Algorithm and Source Code Disclosure Conflict With U.S. Law

Anti-tech and -trade advocates oppose digital trade provisions on algorithm and source codes as they think these prevent governments from enacting public safety, cybersecurity, environmental, and other regulations—when they don’t. The United States does not have a law that requires a source code or algorithm audit as a condition of market entry. Digital trade provisions protecting algorithms and source codes specifically target countries like China that use disclosure as a condition of market access (so they can steal the code and intellectual property) while allowing countries a set of exceptions that address legitimate interests countries have about government operations, national security, and the ability to regulate for public health or other interests.

The letter:

Are you contemplating including in IPEF any terms that could conflict with legislation, regulation, or other government actions relating to digital governance of any kind, including on algorithm and source code secrecy, cross border data flows, location of computing facilities, and non-discriminatory treatment of digital products? If so, please detail the types of legislation, regulation, or actions that could raise potential conflicts under your draft digital trade text if adopted by the U.S. government or our trading partners.

Source code—the coded instructions at the heart of a computer program—enable computer technology to do the amazing things it does. For companies developing software, protecting source code is necessary to prevent other entities from stealing and free riding on the large R&D costs associated with software development. Indicative of the sensitivity around source code is the fact that when one purchases software or goods with software embedded, the software is generally compiled in “object code” form, and not with the actual source code, as this would make it much easier for thieves, hackers, and others to copy and misuse.

The United States and many other countries support provisions on algorithms and source codes as countries, especially China, require companies to transfer or allow access to source code as a condition of market entry—effectively acting as either a barrier to trade or blatant IP theft. Source code is the intellectual property at the heart of modern digital innovation, but as it is digital, it can be easily copied, transferred, and replicated. As in China, the risk of exposure comes from government authorities who pass on part of the code or full copies to local competitors.

Criticism about the impact these provisions have on the government’s ability to regulate ignores the usual framework used in trade agreements to balance the government’s ability to regulate for legitimate public interests with measures to protect against the potential misuse of regulations as trade barriers. For example, the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Trade Agreement states:

This Article does not preclude a regulatory body or judicial authority of a Party from requiring a person of another Party to preserve and make available the source code of software, or an algorithm expressed in that source code, to the regulatory body for a specific investigation, inspection, examination, enforcement action, or judicial proceeding, subject to safeguards against unauthorized disclosure.

What the Letter Ignores: Digital Trade—Especially Digital Exports—Benefit the U.S. Economy and U.S. Workers

Opponents are so blinded by their need to attack and break up U.S. “big tech” that they don’t appear to care about the cost of giving U.S. trading partners carte blanche ability to discriminate against U.S. firms and digital products in terms of exports, competitiveness, and jobs.

Digital trade involves firms of all sizes in every sector, not just big tech—in 2021, the digital economy accounted for an estimated 10.3 percent of U.S. GDP. ). U.S. exports of all services that can be delivered digitally, including business services, were $594 billion in 2021 (75 percent of total U.S. services exports), an increase of 33 percent since 2016. Senator Warren’s home state of Massachusetts is a case in point as its critical biopharma sector—which employed over 106,000 people in 2021, an increase of 13.2 percent from 2020—is dependent on digital tools and data flows for multi-country clinical research that are increasingly impacted by discriminatory restrictions on data flows. The studies that show the economic benefits of traditional trade to the U.S. economy obviously extend to digital trade. Studies show that U.S. multinational firms and their affiliate sales abroad increase U.S. employment by promoting intra-firm exports from parent firms to foreign affiliates. Dartmouth’s Matthew J. Slaughter found that employment and capital investment in U.S. parents and foreign affiliates rise simultaneously via foreign trade and investment. Academic studies for the United States and many other countries have repeatedly found that multinational companies pay higher average compensation than do non-multinationals. In addition, a U.S. Department of Commerce study finds that export-intensive industries pay more on average and the export earnings premium is larger for blue-collar workers in production and support occupations than for white-collar workers in management and professional occupations.

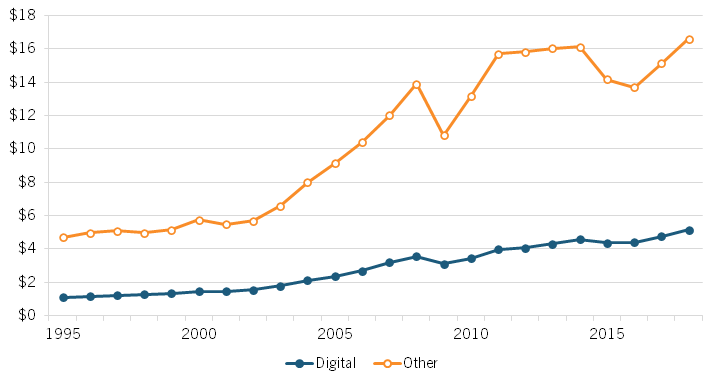

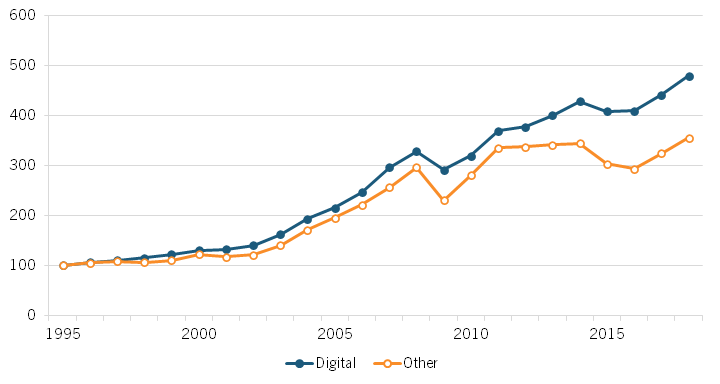

Digital trade’s impact on the U.S. economy is only going to grow. Global digital trade is significant and growing faster than traditional trade—by 2018, digital trade represented 24 percent of global trade. (See figures 1 and 2 below from a recent Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) digital trade policy paper.) It’s clearly in the U.S. interest to ensure that U.S. tech firms and their digital products are protected from discrimination as part of much needed new digital trade rules.

Figure 1: Global trade, digital and non-digital, 1995–2018 ($US trillions)

Figure 2: Change in digital and non-digital global trade, 1995–2018 (indexed; 1995 = 100)

This letter undermines the Biden administration’s efforts to responsibly support U.S. economic and strategic interests in the Indo-Pacific and administration officials should disregard it.

Conclusion

Negotiating new digital trade rules is not some “race to the bottom,” as progressive opponents try and portray it. Quite the opposite. The race to enact new digital trade rules and agreement is led by advanced countries with highly sophisticated regulatory systems like Australia, Canada, Chile, the European Union, Korea, Japan, New Zealand, Japan, Taiwan, and others. Many of these countries are involved in IPEF. If the United States wants to shape new rules and agreements in order to advance key U.S. techno-economic interests it needs to be engaged. Congress obviously has a role in overseeing and shaping U.S. trade and digital policy. If it wants to have a major impact, Congress should enact sensible (and non-discriminatory) digital laws and regulations. Until then, the Biden administration’s digital trade policy should remain based off existing U.S. laws, regulations, and policies.

U.S. techno-economic interests require a commonsense U.S. digital trade agenda. This letter undermines the Biden administration’s efforts to responsibly support U.S. economic and strategic interests in the Indo-Pacific and administration officials should disregard it. Thankfully, there is bipartisan recognition of the role and value of digital trade, including of U.S. efforts to pursue new agreements in the Indo-Pacific. This bipartisan group of congressional representatives should push back against these opponents and the baseless claims they make and ensure that U.S. negotiations have the support and leadership they need to negotiate commonsense digital trade rules.