No, America’s Drug Prices Aren’t Climbing Radically Out of Control

A June 9 New York Times article, “Prices for News Drugs Are Rising 20 Percent a Year. Congress Needs to Act,” authored by Benjamin Rome, Alexander Egilman, and Aaron Kesselheim, substantially mischaracterizes supposedly out-of-control U.S. drug prices as justification for their contention that the federal government should take a much more active role in setting America’s drug prices.

The mischaracterizations start with the fact that the authors offer a sensational headline that prices for these drugs are rising 20 percent annually; but then readily admit the increase is already barely half that (10.7 percent) when more appropriately considering net vs. list prices for drugs.

More fundamentally, the authors analyze only the prices for new—that is, the most innovative, cutting-edge—drugs, such as for oncology or rare diseases, which society should value more highly, while failing to measure overall prescription drug costs or the effects of generic competition. Examining these broader trends shows the consumer price index for pharmaceuticals (and other medical product expenditures) actually decreased slightly from 2008 to 2019. And in fact, Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data show that American consumer’s out-of-pocket drug costs are actually at an all-time low relative to total U.S. health spending.

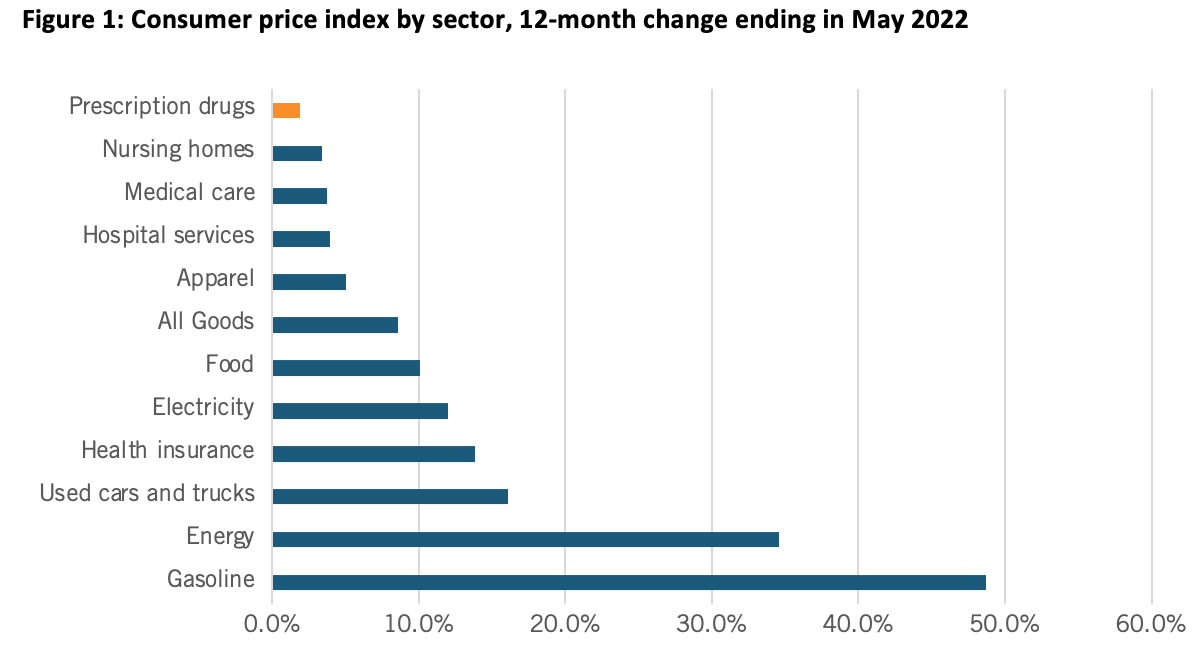

At a March 2022 Senate Finance Committee hearing, proponents of drug price controls attempted to suggest that substantially increasing drug prices were a key contributing factor to U.S. inflation that’s now raging at the highest level in 40 years, to wit the hearing’s title: “Prescription Drug Price Inflation: An Urgent Need to Lower Drug Prices in Medicare.” But increasing prescription drug prices aren’t nearly a significant contributing factor driving U.S. inflation. In fact, over the past 12 months (from May 2021 to May 2022), U.S. prescription drug prices increased only 1.9 percent (which was even lower than their minimal 2.4 percent increase from February 2021 to February 2022). (See Figure 1.) And in fact, between 2020 and 2021, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics recorded zero inflation on prescription drugs and only a 0.8 percent price increase on non-prescription drugs.

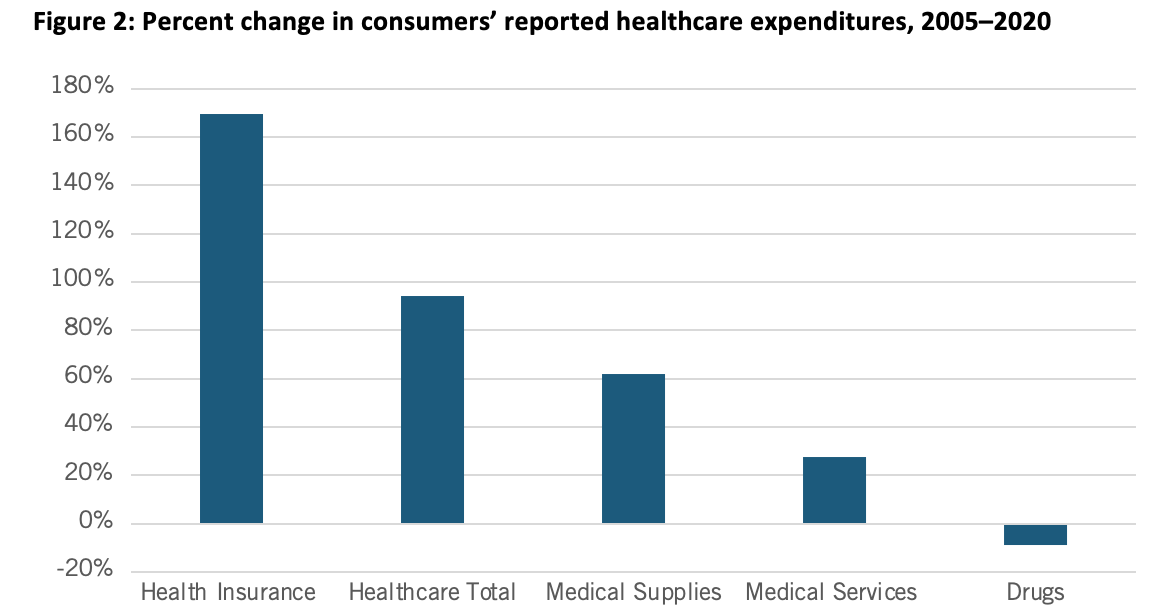

Nor is this recent trend unique. In fact, as calculated by BLS, from 2005 to 2020, Americans’ reported expenditures on health insurance increased by over 160 percent while their total healthcare expenditures increased 94 percent, but consumer expenditures on drugs actually fell by almost 9 percent over that period. (See Figure 2.) Of course, this does not necessarily mean overall drug expenditures fell because health insurance and hospitals also purchase drugs, but it does address consumers’ out-of-pocket costs.

Moreover, the percentage of total U.S. health care spending going toward retail prescription drugs was consistent from 2000 to 2017, at mostly under 10 percent, and even dipped slightly to 8 percent in 2020. Further, Altarum finds that the prescription drug share of national health expenditures should remain stable in the 9 percent range through the remainder of this decade.

The authors further assert that instead of reinvesting profits into research and development (R&D), America’s biopharmaceutical industry focuses more on stock buybacks and advertising. But, in fact, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) finds the sector invests a greater share of revenues, 25.7 percent in 2019, in R&D than any other American industry. As the CBO observes, “By comparison, average R&D intensity across all [U.S.] industries typically ranges between 2 and 3 percent” and even “R&D intensity in the software and semiconductor industries, which are generally comparable to the drug industry in their reliance on R&D, has remained below 18 percent.” In 2019, America’s pharmaceutical industry invested $83 billion in R&D, which, adjusted for inflation, was an amount 10 times greater than the industry spent per year in the 1980s. Moreover, 23 percent of the American biopharmaceutical industry’s workforce can be found at the lab bench in R&D jobs seeking to create new cures, giving the industry a share of employment dedicated to R&D three times higher than the national average. And America’s biopharmaceutical sector alone employs over one-quarter of America’s entire R&D workforce.

Further, the notion that America’s innovative life-sciences industry is spending more on advertising than R&D is fundamentally specious. In contast to the $83 billion in R&D for 2019, total pharmaceutical advertising spending totaled $6.58 billion in 2020 (up only modestly from the $4.9 billion it was in 2007). Moreover this advertising isn’t simply zero-sum, designed to gain market share over competitors. Rather, much of it is about educating consumers—and in the case of biopharma, educating healthcare providers, too—about choices. This is why Frosch et al. find that more than half of physicians agree that ads educate patients about health conditions and available treatments and nearly 75 percent of patient respondents agree that advertisements improve their understanding of diseases and treatments

Nor is the industry excessively profitable. New York University finance professor Aswath Damodaran found that in terms of profitability in 2021 both the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries earned lower returns that the total U.S. market. Similarly, Neeraj Sood found that from 2014 to 2018, wholesalers, insurers, and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) earned higher returns on equity than did the pharmaceutical industry. Thus, the authors are simply flat wrong when they assert that, “Uninhibited U.S. prices have, after all, allowed the pharmaceutical industry to become one of the most profitable sectors in the U.S. economy.”

Perhaps most importantly, the authors assert that drug price controls won’t harm innovation; yet a vast array of academic studies show a reduction in current drug revenues leads to a fall in future research and the number of new drug discoveries. For instance, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Developemnt has found that “there exists a high degree of correlation between pharmaceutical sales revenues and R&D expenditures.” Similarly, Dubois et al. find that every $2.5 billion of additional biopharmaceutical revenue leads to one new drug approval. The assertion that there’s simply no tradeoff between the ability of pharmaceutical companies to earn profits and their ability to invest in future generations of biopharmaceutical innovation is wholly falacious.

Rather, there exists a direct link between the expensive and risky process of drug development and the need to earn commensurate returns on successful drugs to sustain the process. This explains why the CBO estimates that, because of the high failure rates, biopharmaceutical companies need to earn a 61.8 percent rate of return on their successful new drug R&D projects in order to match a 4.8 percent after-tax rate of return on their investments (i.e., a risk-free rate they could readily attain in public markets).

Elsewhere, the authors assert that “in the current situation, brand-name manufacturers set and raise prices as they please.” But that contention is wrong on several accounts. Consider the case of Sovaldi, a breakthrough not just treatment, but an actual cure, for hepatitis C. Certainly Sovaldi was expensive when it was introduced in 2013, at $84,000. However that wasn’t much more than the most-effective treatment available at the time, which cost $70,000, and moreover it represented a fraction of the average cost of $350,000 for patients needing chronic care for Hepatitis C, not to mention a fraction of the $600,000 cost for patients needing a liver transplant. In other words, a hepatitis C cure represented exceptional value at the time, but moreover since 2013 the cost of drugs curing hepatitis C has declined by over half as new competitors entered the market. So one reason companies can’t simply set whatever prices they want is that they face competition.

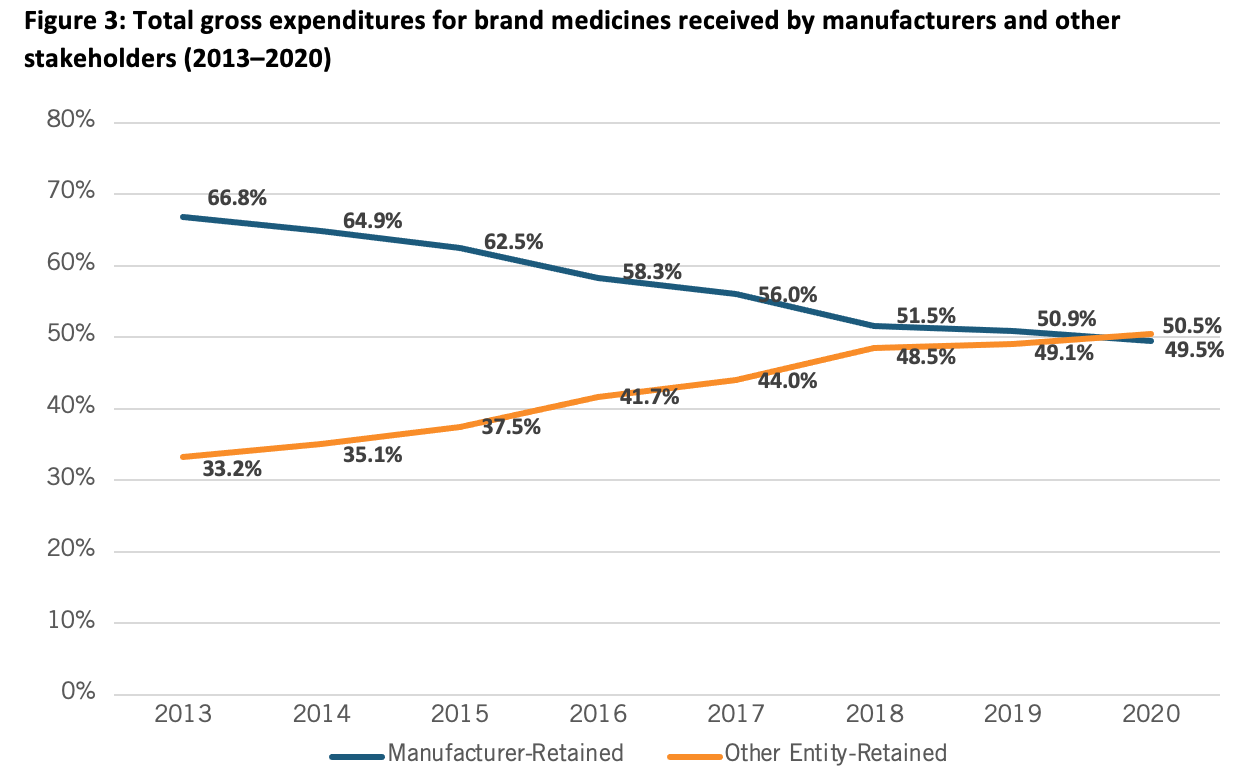

The second point is that when consumers go to the pharmacy, they’re likely buying their medications from one of the leading pharmacy benefit managers, middlemen insurance companies that determine the final out of pocket cost for our medicines (the three largest of which enjoy a 72 percent market concentration). Unfortunately, today America’s PBM system is operating in a way that’s the opposite of what was originally intended: PBMs helping to lower costs. In fact, in 2021, for the first time the share of revenues going to non-manufacturer entities like PBMs in the drug supply chain surpassed the share going to manufacturers. Indeed, since 2013, the share of drug expenditures going to manufacturers has decreased by 17 percentage points. (See Figure 3.) In other words, entities besides biopharmaceutical manufacturers have a significant role in setting the prices Americans pay for medicines, further undermining the contention that drug companies can simply set prices to be whatever they want.

Indeed, drug makers must negotiate with PBMs and other wholesalers to get their drugs listed on formularies like Medicare Part D, where the negotiations are aggressive. Some argue that there’s no negotiation function going on for Medicare Part D drugs, and thus the government needs to take the process over. But the issue isn’t negotiation or no negotiation. There is negotiation, for instance as provided by the PBMs; policymakers should focus on helping this market-based process function better, such as through increasing scrutiny and transparency on PBMs and ensuring they meet their fiduciary obligations.

And while some contend that the Build Back Better Act (BBBA’s) provisions would simply have the government take over the role of handling even-handed drug price negotiations, the reality is the BBBA simply does not establish a true “negotiation” of drug prices in Medicare. Rather, it’s more about arbitrary price setting that would enable the HHS Secretary to dictate prices to manufacturers who would have little or no power to truly negotiate. As the American Action Forum’s Doug Holtz-Eakin elaborates, “The BBBA would enshrine a unique and punitive 95 percent excise tax on gross profits on a therapy if the manufacturer does not agree to the secretary’s demands and set a celing for a drug’s price…Given the 95 percent excise tax the secretary would be free to wield against noncompliant innovators, ‘price extortion’ would be a more honest label for the provision than ‘price negotiation’.” Moreover, unlike past proposals, there would be no floor price below which the secretary would be unable to force further concessions. As Holtz-Eakin continues:

While the BBBA would not apply Medicare’s negotiated prices for drugs to non-federal programs, the most significant implication of the BBBA’s dollar-for-dollar penalties on price increases that exceed the rate of inflation is that, for the first time, the federal government would be unilaterally capping drug prices nationwide, both in federal programs and in the private market. This shift in the federal government’s posture toward private markets, negotiations, and competition cannot be overstated. [Thus]…Significantly under the BBBA the federal government would cap the price of all drugs throughout the entire health care system by penalizing any manufacturer who increases a drug’s price faster than the rate of inflation.

Seeking to bolster their case for the federal govenemnt to take over Medicare drug price negotiations, the authors extol the supposed virtues of European nations’ drug price controls that result in their citizens paying less “for the exact same drugs.” While Europeans may in general pay less, the authors neglect to inform the reader that in many cases Europeans don’t have access to the same drugs Americans do, or only get access to them fat later than Americans. For instance, considering the availability of 356 new medicines introduced since 2011, 87 percent are now available to U.S. patients, compared to just 63 percent in Germany, and that trend applies across the board, from drugs treating cancer on mental illness to those treating rare diseases. This lack of innovative drug access can have serious costs: according to the European Union's own data from 2012, nearly 600,000 European deaths could be avoided each year if the continent’s healthcare systems simply offered “timely and effective medical treatments,” including access to innovative drugs.

The extensive drug price controls European nations have introduced have also cratered their biopharmaceutical indsutries. For instance, in the early 1990s, European and U.S. companies each held about a one-third share of the global drug market. But leadership began to shift in the 1990s. By 2004, Europe’s share would fall to 18 percent, while the U.S. share jumped to 62 percent. And from 1990 to 2017, pharmaceuticals R&D investment in Europe grew 4.5 times, while in the United States, it increased by more than 800 percent. As Nathalie Moll of the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA) writes, “The sobering reality is that Europe has lost its place as the world’s leading driver of medical innovation. Today [January 2020], 47 percent of global new treatments are of U.S. origin compared to just 25 percent emanating from Europe (2014-2018). This represents a complete reversal of the situation just 25 years ago.”

In short, while Europe’s drug price controls certainly lead to lower drug prices—as well as the reality that Europe “free rides” off U.S. biopharmaceutical innovation—one report notes that actually “Europe’s free ride is not free” and illustrates that Europe’s drug price controls actually lead to considerable “social and economic costs in Europe, in the form of delayed access to drugs, poorer health outcomes, decreased investment in research capabilities, and a drain placed on high-value pharmaceutical jobs. Emulating the Euroean approach simply won’t effectively balance the interests of access, affordability, innovation, and vibrant domestic biopharmaceutical industries.

Finally, the authors are correct that some seniors are paying too much for their drugs, but that should be addressed by ensuring that the rebates insurers and PBMs negotiate for Medicare Part D drugs are passed through to seniors at the pharmacy counter and by capping at $2,000 out-of-pocket prescription drug costs on Part D beneficiaries that don’t already qualify for cost-sharing protections (such as through low-income subsidies), not by destroying the successful U.S. biopharmaceutical innovation system.

In conclusion, the United States uniquely leads the world in innovating new drugs and getting them to patients first while sustaining a globally competitive industry and over time making drugs affordable by incentivizing competition and creating generic pathways. America’s market-based, private-enterprise-led, government-supported biomedical innovation system has tremendous strengths. It is both the envy of the world and the source of the majority of the world’s new drugs, benefitting American and global citizens alike. To be sure, some reform is needed—notably to address the pinch seniors are experiencing in out-of-pocket costs at the pharmacy counter—but radical reconstructive surgery in the form of stringent drug price controls is not.