Comments Before the US Senate Help Committee Regarding the “Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act”

Contents

The Failed Effort to Include Reasonable Pricing Provisions in NIH CRADAs. 1

The Failure of Reasonable Pricing Clauses in Zika Vaccine Commercialization. 4

The Misguided Effort to Leverage Bayh-Dole March-In Rights for Price Controls 5

Introduction

This submission represents the views of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF), a non-profit, non-partisan think tank focused on the intersection of technological innovation and public policy.

ITIF has serious reservations regarding provisions proposed in draft legislation for the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act (PAHPA Act) that would cap the U.S. cost of any products resulting from U.S. Health and Human Services (HHS) Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) or Centers for Disease Control (CDC) funding “at the lowest price among G7 countries” (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States) and do so “at a reasonable price.” Policymakers should reject the inclusion of these provisions in the PAHPA Act, recognizing the long history of failure with efforts to include reasonable pricing clauses in NIH licensing activities.

The Failed Effort to Include Reasonable Pricing Provisions in NIH CRADAs

The debate around “reasonable pricing” of drugs stemming from licensed research goes back some time. The Federal Technology Transfer Act of 1986 (FTTA) authorized federal laboratories to enter into Cooperative Research and Development Agreements (CRADAs) with numerous entities, including private businesses. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) has found that CRADAs “significantly advance biomedical research by allowing the exchange and use of experimental compounds, proprietary research materials, reagents, scientific advice, and private financial resources between government and industry scientists.”[1]

In 1989, NIH’s Patent Policy Board adopted a policy statement and three model provisions to address the pricing of products licensed by public health service (PHS) research agencies on an exclusive basis to industry, or jointly developed with industry through CRADAs. In doing so, the Department of Health and Human Services (then, DHHS) became the only federal agency at the time (other than the Bureau of Mines) to include a “reasonable pricing” clause in its CRADAs and exclusive licenses.[2] The 1989 PHS CRADA Policy Statement asserted:

DHHS has a concern that there be a reasonable relationship between pricing of a licensed product, the public investment in that product, and the health and safety needs of the public. Accordingly, exclusive commercialization licenses granted for the NIH/ADAMHA [Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration] intellectual property rights may require that this relationship be supported by reasonable evidence.

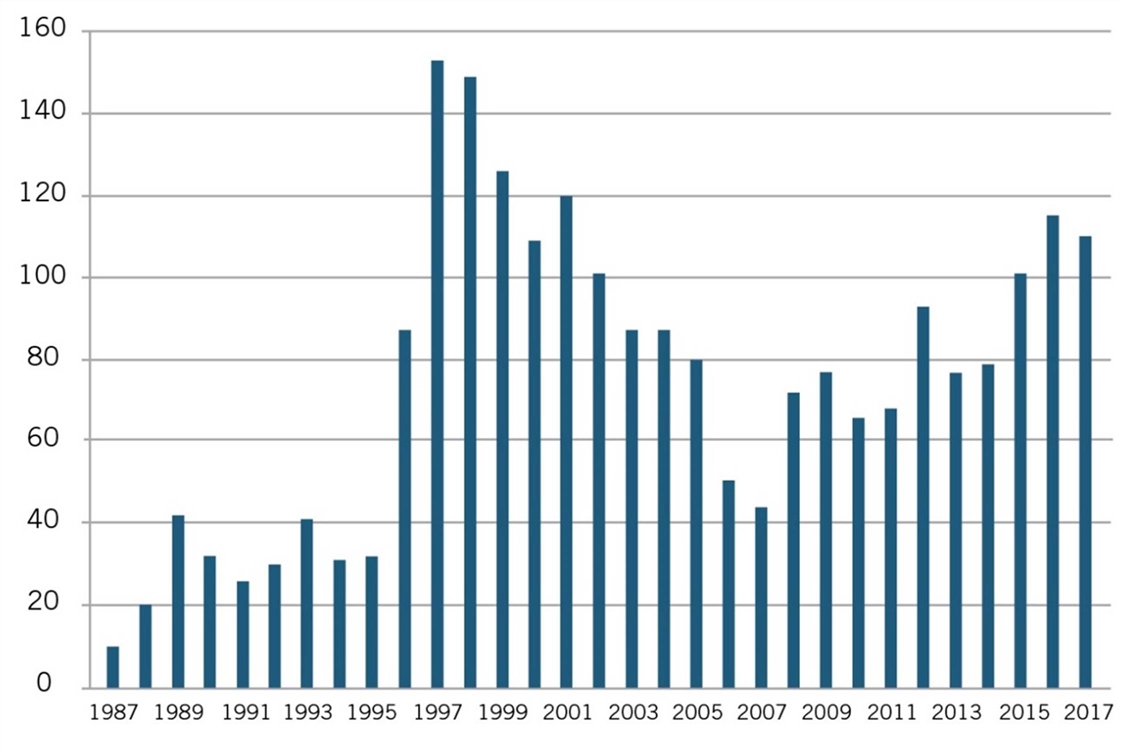

But as Joseph P. Allen notes, such “attempts to impose artificial ‘reasonable pricing’ requirements on developers of government supported inventions did not result in cheaper drugs. Rather, companies simply walked away from partnerships.”[3] Use of CRADAs began in 1987 and rapidly increased until the reasonable pricing requirement hit in 1989, after which they declined through 1995. (See figure 1.)

Figure 1: Private-sector CRADAs with NIH, 1987–2017[4]

Recognizing that the only impact of the reasonable pricing requirement was undermining scientific cooperation without generating any public benefits, NIH eliminated the reasonable pricing requirement in 1995. In removing the requirement, then NIH director Dr. Harold Varmus explained, “An extensive review of this matter over the past year indicated that the pricing clause has driven industry away from potentially beneficial scientific collaborations with PHS scientists without providing an offsetting benefit to the public. Eliminating the clause will promote research that can enhance the health of the American people.”[5] As figure 1 shows, after NIH eliminated the requirement in 1995, the number of CRADAs immediately rebounded in 1996, and grew considerably in the following years.[6] Moreover, NIH showed the damage went beyond just CRADAs and licenses:

The “reasonable pricing” clause, however, discourages the execution of exclusive licenses and CRADAs and inhibits the ability of PHS scientists to obtain access to research materials and scientific expertise from their private sector counterparts, even outside the context of a license or a CRADA.[7]

The case represents a natural experiment showing the harm pricing requirements can inflict. Somewhat similarly, as the California Senate Office of Research has noted, “Granting agencies such as the National Institutes of Health ultimately have abandoned policies that require a financial return to the government after concluding that removing barriers to the rapid commercialization of products represents a greater public benefit than any potential revenue stream to the government.”[8] And while some have contended “the agency [NIH] removed it [the reasonable pricing clause] in 1995 following industry pushback” the reality is that the agency didn’t repeal the clause because of industry pushback; it repealed it because the approach simply doesn’t work and moreover harms the process of biopharmaceutical innovation in the United States.[9]

The Failure of Reasonable Pricing Clauses in Zika Vaccine Commercialization

A more recent case involved biopharmaceutical company Sanofi possibly taking a license from the U.S. Army to develop a vaccine for the Zika virus. U.S. Army scientists from the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research developed two candidate vaccines for the Zika virus and posted a notice in the federal register offering to license them on either a nonexclusive or exclusive basis. No company responded to the nonexclusive license, and Sanofi was the only company that submitted a license application for the Army’s Zika candidate vaccine, with the U.S. Army and Sanofi reaching a licensing agreement in June 2016 that would enable Sanofi to continue the development and clinical trial work necessary to turn the candidate vaccine into a market-ready product. As a U.S. Army official noted, “Exclusive licenses are often the only way to attract a competent pharma partner for such development projects,” and are needed because the military lacks “sufficient” research and production capabilities to develop and manufacture a Zika vaccine.[10] Sanofi received a $43 million government grant to start undertaking clinical trial work on the virus candidate.

In July 2017, supported by Knowledge Economy International, an organization opposed to intellectual property rights, Sens. Bernie Sanders (D-VT) and Dick Durbin (D-IL) argued that the U.S. Army and Sanofi should insert reasonable pricing language into the exclusive license. Sanders even called on President Trump to cancel the deal.[11] In response, Army officials noted that they were not in a position to “enforce future vaccine prices.” For its part, Sanofi representatives noted, “We can’t determine the price of a vaccine that we haven’t even made yet,” and argued that “it’s premature to consider or predict Zika vaccine pricing at this early stage of development. As noted earlier, ongoing uncertainty around epidemiology and disease trajectory make any commercial projections theoretical at best.”[12] Sanofi noted that it had committed over 60 researchers to the effort, invested millions of dollars itself, and was “committed to leveraging its flavivirus vaccine development and manufacturing expertise to deliver and ultimately price a Zika vaccine in a responsible way.”[13]

Sanofi also noted that the proposed license would require it to pay milestone and royalty payments back to the government, and its exclusive license would not prevent other companies—such as GlaxoSmithKline, Takeda, and Moderna, which also had all struck their own Zika vaccine partnerships with U.S. agencies—from bringing competing products to market, and allow for robust competition in the market for Zika vaccines.[14] However, with both partners continuing to be attacked in the media, in September 2017, Sanofi announced it would “not continue development of, or seek a license from, the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research for the Zika vaccine candidate at this time.”[15] This is yet another case wherein certain policymakers’ insistence on pricing requirements stifled innovation and the potential for a firm to bring a promising innovation to market, in the process precluding innovative, patient-benefitting medicines from reaching the public.

The Misguided Effort to Leverage Bayh-Dole March-In Rights for Price Controls

The failed experiment to include reasonable pricing clauses in NIH CRADAs is yet another reason to reject advocates’ calls to leverage Bayh-Dole Act march-in right provisions for purposes of seeking “reasonable” or “lower” drug prices. The Bayh-Dole Act, passed in 1980, affords contractors—such as universities, small businesses, and nonprofit research institutions—rights to the intellectual property generated from federal funding. It has been called “Possibly the most inspired piece of legislation to be enacted in America over the past half-century.”[16] A provision within the Bayh-Dole Act specifies “march-in rights” that permit the government, in extremely proscribed circumstances, to require patent holders to grant a “nonexclusive, partially exclusive, or exclusive license” to a “responsible applicant or applicants.”[17]

The Bayh-Dole Act’s architects principally intended for march-in rights to be used to ensure patent owners commercialized their inventions.[18] As Senator Birch Bayh explained:

When Congress was debating our approach fear was expressed that some companies might want to license university technologies to suppress them because they could threaten existing products. Largely to address this fear, we included the march-in provisions.[19]

Moreover, as Senators Bayh and Dole have themselves noted, the Bayh-Dole Act’s march-in rights were never intended to control or ensure “reasonable prices.”[20] As the twain wrote in a 2002 Washington Post op-ed titled, “Our Law Helps Patients Get New Drugs Sooner,” the Bayh-Dole Act:

Did not intend that government set prices on resulting products. The law makes no reference to a reasonable price that should be dictated by the government. This omission was intentional; the primary purpose of the act was to entice the private sector to seek public-private research collaboration rather than focusing on its own proprietary research.[21]

The op-ed reiterated that the price of a product or service was not a legitimate basis for the government to use march-in rights, noting:

The ability of the government to revoke a license granted under the act is not contingent on the pricing of a resulting product or tied to the profitability of a company that has commercialized a product that results in part from government-funded research. The law instructs the government to revoke such licenses only when the private industry collaborator has not successfully commercialized the invention as a product.[22]

Rather, Bayh-Dole’s march-in provision was designed as a fail-safe for limited instances in which a licensee might not be making good-faith efforts to bring an invention to market, or when national emergencies require that more product is needed than a licensee is capable of producing. As Joe Allen, a senate staffer for Bayh who played a key role in shaping the legislation, explains, Congress’s introduction of Bayh-Dole was intended “to decentralize patent management from the bureaucracy into the hands of the inventing organizations, while retaining the long-established precedent that march-in rights were to be used in rare situations when effective efforts are not being made to bring an invention to the marketplace or enough of the product is not being produced to meet public needs.”[23]

March-in rights have never been exercised during the over-40-year history of the Bayh-Dole Act.[24] NIH has denied all seven petitions to apply march-in rights, noting that the drugs in question were in virtually all cases adequately supplied and that concerns over drug pricing were not, by themselves, sufficient to provoke march-in rights.[25] NIH itself has expressed skepticism about the use of march-in rights to control drug prices, noting:

Finally, the issue of the cost or pricing of drugs that include inventive technologies made using federal funds is one which has attracted the attention of Congress in several contexts that are much broader than the one at hand. In addition, because the market dynamics for all products developed pursuant to licensing rights under the Bayh-Dole Act could be altered if prices on such products were directed in any way by NIH, the NIH agrees with the public testimony that suggested that the extraordinary remedy of march-in is not an appropriate means of controlling prices.[26]

As John Rabitschek and Norman Latker write in “Reasonable Pricing—A New Twist for March-in Rights Under the Bayh-Dole Act” in the Santa Clara University High Technology Law Journal, “A review of the [Bayh-Dole] statute makes it clear that the price charged by a licensee for a patented product has no direct relevance to march-in rights.”[27] As the authors conclude:

There is no reasonable pricing requirement under 35 U.S.C. §203(l)(a)(1), considering the language of this section, the legislative history, and the prior history and practice of march-in rights. Rather, this provision is to assure that the contractor utilizes or commercializes the funded invention.[28]

The argument that Bayh-Dole march-in rights could be used to control drug prices was originally advanced in an article by Peter S. Arno and Michael H. Davis.[29] They contended that “[t]he requirement for ‘practical application’ seems clear to authorize the federal government to review the prices of drugs developed with public funding under Bayh-Dole terms and to mandate march-in when prices exceed a reasonable level” and suggested that under Bayh-Dole, the contractor may have the burden of showing that it charged a reasonable price.[30] While Arno and Davis admitted there was no clear legislative history on the meaning of the phrase “available to the public on reasonable terms,” they still concluded that, “[t]here was never any doubt that this meant the control of profits, prices, and competitive conditions.”[31]

But as Rabitschek and Latker explain, there are several problems with this analysis. First, the notion that “reasonable terms” of licensing means “reasonable prices” arose in unrelated testimony during the Bayh-Dole hearings. Most importantly, they note, “If Congress meant to add a reasonable pricing requirement, it would have explicitly set one forth in the law, or at least described it in the accompanying reports.”[32] As Rabitschek and Latker continue, “There was no discussion of the shift from the ‘practical application’ language in the Presidential Memoranda and benefits being reasonably available to the public, to benefits being available on reasonable terms under 35 U.S.C. § 203.”[33] As they conclude, “The interpretation taken by Arno and Davis is inconsistent with the intent of Bayh-Dole, especially since the Act was intended to promote the utilization of federally funded inventions and to minimize the costs of administering the technology transfer policies…. [The Bayh-Dole Act] neither provides for, nor mentions, ‘unreasonable prices.’”[34]

It also takes the debate back to the central point that, in their push for lower drug prices through weaker private IP rights stemming from federally funded research, advocates fail to realize that no drugs were created from federally funded inventions under the previous (to Bayh-Dole) regime.[35] Aware as early as the mid-1960s that the billions of dollars the federal government was investing in research and development was not paying the expected dividends, President Johnson in1968 asked Elmer Staats, then the comptroller general of the United States, to analyze how many drugs had been developed from NIH-funded research. Johnson was stunned when Staats’s investigation revealed that “not a single drug had been developed when patents were taken from universities [by the federal government].”[36] In contrast, well over 200 new drugs and vaccines have been developed through public-private partnerships facilitated in part by the Bayh-Dole Act since its enactment in 1980.[37]

Creating innovative drugs is a risky, lengthy, and expensive process that can take 15 or more years at a cost approaching $3 billion.[38] Over 90 percent of drug candidates fail in the clinical trial phase.[39] Mandating reasonable prices or weakening the certainty of access to IP rights provided under Bayh-Dole to address drug pricing issues—especially if it meant a government entity could walk in and retroactively commandeer innovations private-sector enterprises invested hundreds of millions, if not billions, to create—would significantly diminish private businesses’ incentives to commercialize products supported by federally funded research.[40] As David Bloch notes, “The reluctance of such [biopharmaceutical] companies to do business with the government is almost invariably tied up in concerns over the government’s right to appropriate private sector intellectual property.”[41] As he continues, “Each march-in petition potentially puts at risk the staggeringly massive investment that branded pharmaceutical companies make in developing new drug therapies.”[42] Put simply, using march-in rights to control drug prices could seriously compromise medical discovery and innovation.

In conclusion, mandating the inclusion of reasonable pricing clauses in NIH licensing activities is an approach that has abjectly failed in the past and has continued to inhibit biopharmaceutical technology commercialization in the rare instances in which it’s been applied since. America’s biopharmaceutical innovation system leads the world, as over the past two decades, U.S.-headquartered biopharmaceutical enterprises accounted for almost half of the world’s new drugs.[43] The United States has built a world-leading biomedical innovation system in part throuh the technology transfer and commercialization pathways the Bayh-Dole Act has created and the technology transfer procesess that have been built up to support it at NIH, the Departments of Defense and Energy, and other federal ageneices. The system is working and policymakers should not disrupt it by including reasonable pricing language in the PAHPA Act.

Thank you for your consideration.

Endnotes

[1]. National Institutes of Health, “NIH News Release Rescinding Reasonable Pricing Clause,” news release, April 11, 1995, https://www.ott.nih.gov/sites/default/files/documents/pdfs/NIH-Notice-Rescinding-Reasonable-Pricing-Clause.pdf.

[2]. Ibid.

[3]. Joe Allen, “Compulsory Licensing for Medicare Drugs—Another Bad Idea from Capitol Hill,” IP Watchdog, August 23, 2018, http://www.ipwatchdog.com/2018/08/23/compulsory-licensing-medicare-drugs-bad-idea/id=100608/.

[4]. National Institutes of Health, “OTT Statistics,” accessed January 13, 2019, https://www.ott.nih.gov/reportsstats/ott-statistics.

[5]. National Institutes of Health, “NIH News Release Rescinding Reasonable Pricing Clause.”

[6]. Allen, “Compulsory Licensing for Medicare Drugs—Another Bad Idea from Capitol Hill.”

[7]. National Institutes of Health, “NIH News Release Rescinding Reasonable Pricing Clause.”

[8]. California Senate Office of Research, “Optimizing Benefits From State-Funded Research” Policy Matters (March 2018), 12, https://sor.senate.ca.gov/sites/sor.senate.ca.gov/files/0842%20policy%20matters%20Research%2003.18%20Final.pdf.

[9]. Lecia Bushak, “Bernie Sanders puts NIH nom in crosshairs over drug pricing fight,” Haymarket Marketing Communications, June 16, 2023, https://www.mmm-online.com/home/channel/regulatory/bernie-sanders-puts-nih-nom-in-crosshairs-over-drug-pricing-fight/.

[10]. Eric Sagonowsky, “Sanofi Pulls Out of Zika Vaccine Collaboration as Feds Gut its R&D Contract,” FiercePhrma, September 1, 2017, https://www.fiercepharma.com/vaccines/contract-revamp-sanofi-s-Zika-collab-u-s-government-to-wind-down; Ed Silverman, “Sanofi Rejects U.S. Army Request for ‘Fair” Pricing’ for a Zika Vaccine,” PBS, May 20, 2017, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/sanofi-army-request-pricing-Zika-vaccine.

[11]. Bernie Sanders, “Trump Should Avoid a Bad Zika Deal,” The New York Times, March 10, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/10/opinion/bernie-sanders-trump-should-avoid-a-bad-Zika-deal.html?_r=0.

[12]. Eric Sagonowsky, “Sanofi Executive Lays Out Case For Taxpayer Funding—And Exclusive Licensing—on Zika Vaccine R&D,” FiercePhrma, May 25, 2017, https://www.fiercepharma.com/vaccines/exec-says-corporate-responsibility-not-potential-profits-drove-sanofi-s-Zika-vaccine-r-d.

[13]. Jeannie Baumann, “Sanofi Never Rejected Fair Pricing for Zika Vaccine: Exec,” BloombergNews, July 18, 2017, https://www.bna.com/sanofi-rejected-fair-n73014461930/.

[14]. Sagonowsky, “Sanofi Executive Lays Out Case For Taxpayer Funding—And Exclusive Licensing—on Zika Vaccine R&D.”

[15]. Sagonowsky, “Sanofi Pulls Out of Zika Vaccine Collaboration as Feds Gut its R&D Contract.”

[16]. “Innovation’s Golden Goose,” The Economist, December 12, 2002, http://www.economist.com/node/1476653.

[17]. John R. Thomas, “March-In Rights Under the Bayh-Dole Act” (Congressional Research Service, August 2016), 7, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44597.pdf.

[18]. David S. Bloch, “Alternatives to March-In Rights” Vanderbilt Journal of Entertainment and Technology Law Vol. 18, Issue 2, (2016): 253, https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/jetlaw/vol18/iss2/2/.

[19]. Statement of Senator Birch Bayh to the National Institutes of Health (May 24, 2004), https://www.ott.nih.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2004NorvirMtg/2004NorvirMtg.pdf.

[20]. Birch Bayh, “Statement of Birch Bayh to the National Institutes of Health,” May 25, 2014, http://www.essentialinventions.org/drug/nih05252004/birchbayh.pdf.

[21]. Birch Bayh and Bob Dole, “Our Law Helps Patients Get New Drugs Sooner,” The Washington Post, April 11, 2002, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/2002/04/11/our-law-helps-patients-get-new-drugs-sooner/d814d22a-6e63-4f06-8da3-d9698552fa24/.

[22]. Ibid.

[23]. Joseph P. Allen, “When Government Tried March In Rights to Control Health Care Costs,” IPWatchdog, May 2, 2016, http://www.ipwatchdog.com/2016/05/02/march-in-rights-health-care-costs/id=68816/.

[24]. Ibid.

[25]. Thomas, “March-In Rights Under the Bayh-Dole Act,” 11–12.

[26]. Elias A. Zerhouni, director, NIH, “In the Case of Norvir Manufactured by Abbott Laboratories, Inc.,” July 29, 2004, http://www.ott.nih.gov/sites/default/files/documents/policy/March-In-Norvir.pdf.

[27]. John H. Rabitschek and Norman J. Latker, “Reasonable Pricing—A New Twist for March-in Rights Under the Bayh-Dole Act,” Santa Clara High Technology Law Journal Vol. 22, Issue 1 (2005), 160, https://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1399&context=chtlj.

[28]. Ibid, 167.

[29]. Peter Amo and Michael Davis, “Why Don’t We Enforce Existing Drug Price Controls? The Unrecognized and Unenforced Reasonable Pricing Requirements Imposed upon Patents Deriving in Whole or in Part from Federally Funded Research,” Tulane Law Review Vol. 75, 631 (2001), https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1754&context=fac_articles.

[30]. Ibid.

[31]. Rabitschek and Latker, “Reasonable Pricing,” 162–163.

[32]. Ibid, 163.

[33]. Stephen Ezell, “The Bayh-Dole Act’s Vital Importance to the U.S. Life-Sciences Innovation System” (ITIF, March 2019), 24, https://www2.itif.org/2019-bayh-dole-act.pdf. Here, the Presidential Memoranda refers to memoranda produced by the Kennedy and Nixon administrations that pertained to government policy related to contractor ownership of inventions.

[34]. Rabitschekand Latker, “Reasonable Pricing,” 163.

[35]. Joseph Allen, “Bayh-Dole Under March-in Assault: Can It Hold Out?” IP Watchdog, January 21, 2016, http://www.ipwatchdog.com/2016/01/21/bayh-dole-under-march-in-assault-can-it-hold-out/id=65118/.

[36]. Allen, “When Government Tried March In Rights to Control Health Care Costs.”

[37]. Association of University Technology Managers (AUTM), “Driving the Innovation Economy: Academic Technology Transfer in Numbers,” https://www.autm.net/AUTMMain/media/SurveyReportsPDF/AUTM-FY2016-Infographic-WEB.pdf.

[38]. Deloitte Center for Health Solutions, “Unlocking R&D Productivity: Measuring the Return From Pharmaceutical Innovation 2018” (Deloitte Center for Health Solutions, 2018), https://www2.deloitte.com/global/en/pages/life-sciences-and-healthcare/articles/measuring-return-from-pharmaceutical-innovation.html.

[39]. Duxin Sun et al., “Why 90% of clinical drug development fails and how to improve it?” Acta Pharmaceutical Sinica B Vol. 12, Issue 7 (July 2022), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9293739/.

[40]. Stephen J. Ezell, “Why Exploiting Bayh-Dole ‘March-In’ Provisions Would Harm Medical Discovery,” The Innovation Files, April 29, 2016, https://itif.org/publications/2016/04/29/why-exploiting-bayh-dole-%E2%80%9Cmarch-%E2%80%9D-provisions-would-harm-medical-discovery/.

[41]. Bloch, “Alternatives to March-In Rights,” 261.

[42]. Ibid.

[43]. Stephen Ezell, “Testimony to the Senate Finance Committee on “Prescription Drug Price Inflation” (ITIF, March 16, 2022), https://itif.org/publications/2022/03/16/testimony-senate-finance-committee-prescription-drug-price-inflation/.